Écriture Feminine in the Calligraphies of Pouran Jinchi

In this short review, Delaram Hosseinioun analyses the calligraphies of the Persian artist Pouran Jinchi. She argues how Jinchi's art extends the écriture feminine or the notion of feminine voice defined by the French philosopher Helen Cixous.

Born in 1959 in Mashhad, one of the most conservative cities of the country, Pouran Jinchi initially trained as a calligrapher. In an interview she said, “I learned traditional calligraphy as a young child, without that knowledge, I would not be the artist I am today. My art is reflective of my life experiences from childhood to now.” (interview with Islamic Arts Magazine, 2013).

Jinchi went on to receive her bachelor in Civil Engineering from George Washington University in 1982. Later, in 1989, she rebelled against this traditional career path and began her studies in sculpture and painting at the University of California, Los Angeles. Rather than discarding her calligraphic background, Jinchi chose to recast it: “For some, calligraphy could be a symbolic meaning, but for me, it is an interpretation.” (interview with Islamic Arts Magazine, 2013).

In this review, I analyse Jinchi’s work through the perspective of French philosopher Hélène Cixious. By deconstructing language as a symbol of patriarchy, Cixous confronts the privileged male discourse over the female identity. Highlighting the value of an authentic feminine utterance, Cixous argues that écriture féminine or female writing is the medium which permits women, the marginalised Others of the society, to access their inner self and reclaim their liberty. Cixous believes, “writing is precisely the very possibility of change, the space that can serve as a springboard for subversive thought, the precursory movement of a transformation of social and cultural structures.” (“Laugh of Medusa” 879)

Cixous wrote of her own life, “Now, I believed as one should in the principle of identity, of non-contradiction, of unity. For years I aspired to this divine homogeneity. I was there with my big pair of scissors, and as soon as I saw myself overlapping, snip, I cut, I adjusted, I reduced everything to a personage known as ‘a proper woman’.” ("Coming to Writing" and Other Essays, 30)

Throughout the epochs, Persian calligraphy has always been associated with and dominated by male artists. Jinchi’s art stands as a challenge to this historical convention. She notes:

| I am fascinated with how we use words to make sense of the world, to communicate with one another, and to cover up the essence of things. In this sense, any language can be turned into art and can be read universally. There is a tension in my calligraphic art, because it is always illegible. So even those who can read Persian can’t really read the texts in my artworks. But the sensibility in my art is open to broader interpretation and can be read universally. (Interview with Art Radar, 2016) |

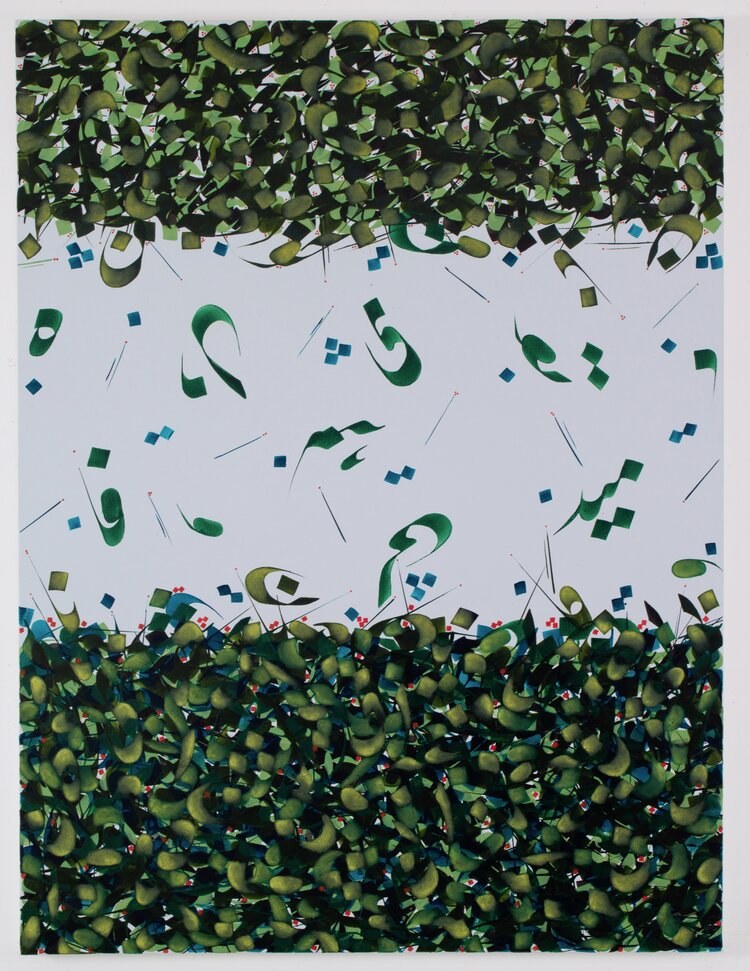

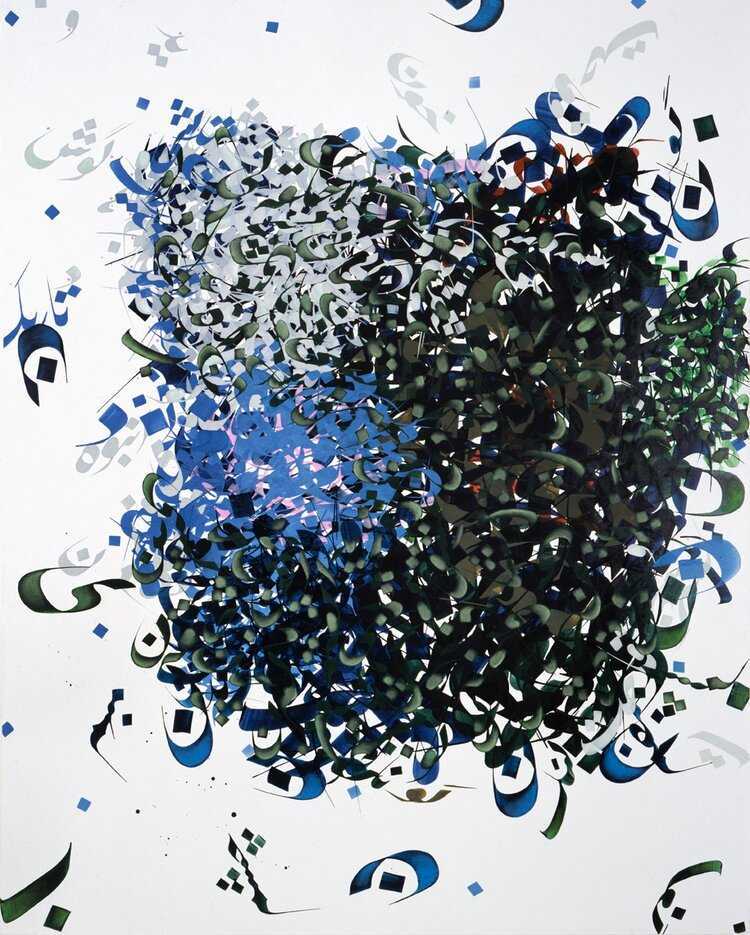

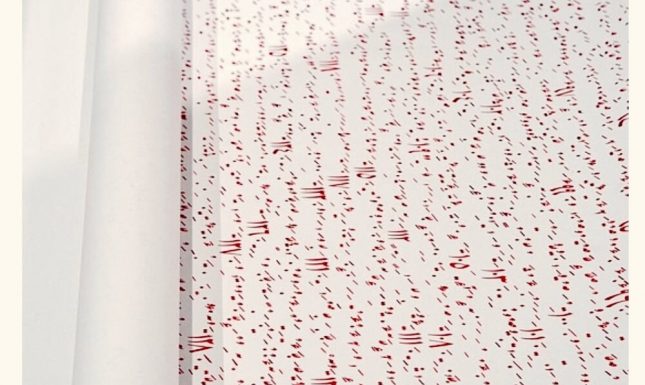

Through her art, the sharp and solid edges of classic scripts blur into the artist’s subconscious and are replaced by floating shapes. The resulting aesthetic chaos grants the artist an opportunity to announce all suppressed feelings and lures her spectator into a mesmerising visual vortex.

Jinchi’s calligraphy always has historic and literary references. She notes, “I almost feel I am a writer, I don't have any words, I am a writer with no words. I basically use words, poems or other literary works. I deconstruct words to say what I have to say.” (Interview with DH, 2021)

She takes some of the most iconic Persian masterpieces the audience bonded with – such as the poetry of Forough Farroukhzad, the most symbolic representation of the feminine voice, and The Blind Owl by Sadegh Hedayat, one of the most controversial modern literary works that shattered the patriarchy – to deconstruct old-fashioned approaches. For Jinchi, words in their limited frame fail the meanings their creators envisioned. The words become more like pigments to carry sentiments. Her art conveys the magnitude of those narratives through the feminine view.

As a genderless language, Farsi is among languages in which the male voice has no dominancy over the female one, nor do the words carry genders. Through her modern and radical approach, Jinchi deconstructs all the classic calligraphy norms and renders a new artistic and feminine soul to the words. Jinchi adds, “for me, I never really thought of words or calligraphy as being gendered, I thought of it as my right.” (interview with DH 2021)

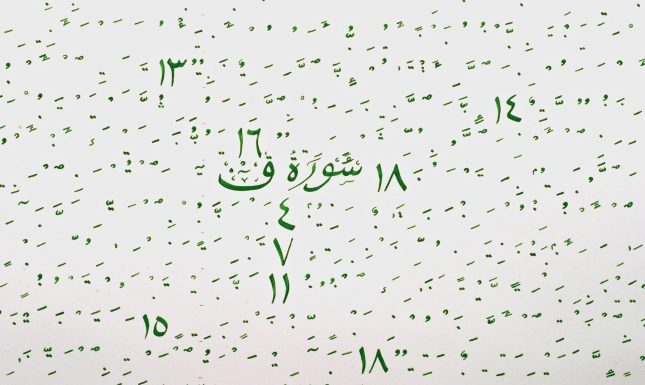

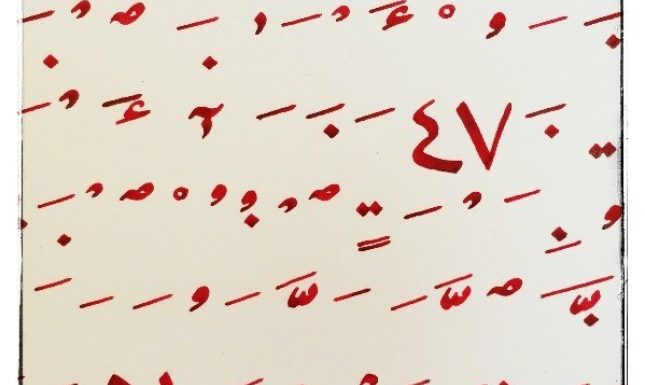

In Recitation Scroll, she portrays one of the Quran’s surat, or chapters, eliminating all the words and merely depicting the phonetic vowels. In Farsi these vowels are invisible, but in Arabic, an extremely gender-based language, they are indicated, and change the meaning of the word if eliminated. She thereby challenges the determined means of expressions, along with the concept of visibility. Based on feminine écriture, loss of words draws attention to the limits of language in expressing women’s dynamism; hence women’s silence is not a symbol of lack but rather reveals language’s limited capacity towards the magnitude of female utterance.

By juxtaposing the male-oriented art of calligraphy with conceptual art, Jinchi deconstructs classical narratives through minimalism, but at the same time she adheres to the aesthetics of sentiments and feminine subtlety. Thus, through this pictorial écriture feminine she not only challenges restrictions but also frees the feminine voice from the cliché of the being chaotic. Through her calligraphies, Jinchi urges the new generation of women to create their own narratives and exceed the invisible patriarchal frames imposed on language.

All images courtesy of Pouran Jinchi. Want to read more? Have a look at the interview with Pouran Jinchi by Delaram Hosseinioun at Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies.

0 Comments