A Blind Dean of Arabic Literature: The Legacy of Taha Hussein

In 1979, millions of Egyptians huddled in front of their TVs to watch a series about the life of a blind man from a village in Upper Egypt who fought against poverty and ignorance to become a symbol of enlightenment in post-colonial Egypt: Taha Hussein.

The Egyptian state television aired the series which was based on his autobiography Al-Ayyam (The Days) while Egypt was getting ready to participate in the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981. For most Egyptians, Taha Hussein (1889-1973) is simply a voice of our own. Born to a poor family in one of the least privileged territories of Egypt, his family sent him to a small local Quran school and then to Al-Azhar University hoping that one day he could make a living either by reciting the Quran or as a teacher.

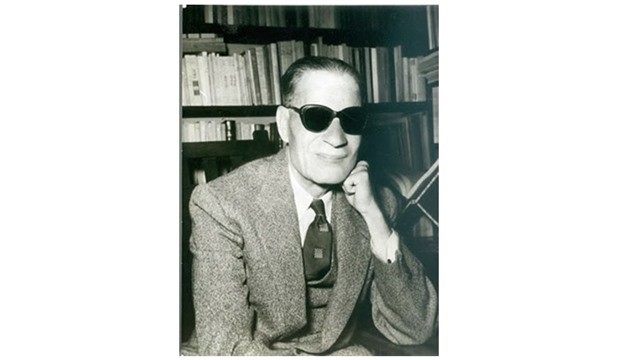

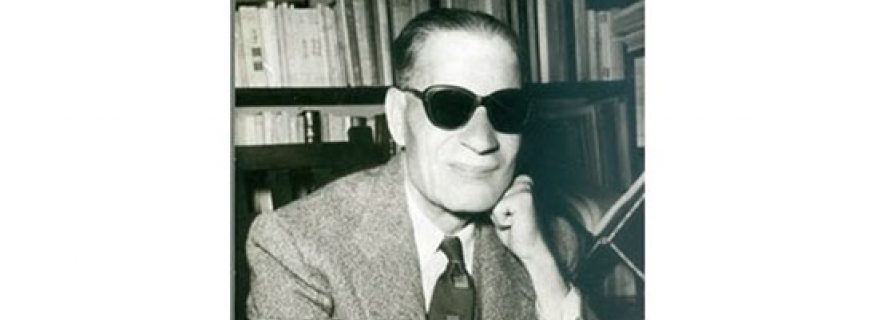

Taha Hussein in his iconic photo with black glasses

His legacy does not stop at his struggle with blindness. Egyptian parents usually present him as an example to their children: a poor boy born in 1889 who became the first to hold a PhD degree from Cairo University. After a vicious fight with his conservative educators, Hussein received a scholarship and obtained a second PhD degree from the Sorbonne in 1919. With Hussein’s story, Egyptian parents remind their children that disability, economic hardship and even social and economic injustice are no excuses for failure.

Public education in Egypt is preserving the legacy of Hussein as much as parents do. In all pre-university grades, students learn about his biography, short stories and articles in the curricula of Arabic and Egyptian modern history. When a new project or facility is established in Egypt to support the blind society his name comes first: from the special Taha Hussein library at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina to small special schools in the Nile Delta.

Hussein was very committed to his students and their education until his death in 1973. When he became minister of Education in 1950, he issued a decree to abolish all fees in public and vocational secondary schools. Earlier in 1944 he served as a consultant to the minister of Education, who implemented Hussein’s recommendation to abolish primary education fees.

Today, 18 million Egyptian students are enrolled in free public schools thanks to Taha Hussein, who believed that the costs of education were the biggest obstacle hindering Egyptian families from sending their children to schools. His famous quote “education is like the water we drink and the air we breathe” is clearly written and raised on school and university walls and on the back covers of schoolbooks.

He never minded a battle nor tried to use his disability as a justification or escape from his rivals’ attacks. When the famous cinema producer Aziza Amir tried to acquire the intellectual rights of his novels to produce them as films, Hussein insisted on adding a contract condition that enabled him to interfere in the director’s vision of the scenario whenever he felt necessary.

His blindness did not save him from being accused of blasphemy, which eventually led to his termination as dean of Cairo University’s Faculty of Arts in 1932. The reason for this was the publication of his most controversial book of literary criticism Fi Alsher Algaheli (Pre-Islamic Poetry), in which he questioned the authenticity of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry.

Despite the massive change of the political and social Egyptian scene after the 1952 revolution, Hussein’s status and respect in governing circles did not change. Although he was no longer a minister, the new regime used his voice and example to support its socialist and nationalist agenda.

Yet Hussein had his ups and downs with the new rulers. Due to his critical comments on the writings of president Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1964, he was fired from his position as chief editor of the newspaper Al Gomhuria, the mouthpiece of the new regime. One year later, however, he was decorated with the “Necklace of the Nile”, the highest civilian Egyptian decoration, a decision by the nationalist regime which appeared as an apology to one of the great minds of the nation.

President Gamal Abdelnasser of Egypt honors Taha Hussein with the "Necklace of the Nile," the highest Egyptian decoration in 1965

The most striking element of Taha Hussein’s legacy will always be that his disability became completely irrelevant in the encounters with his intellectual and political rivals. If it were not for his iconic picture with his eyes hidden behind his black glasses, we would have

only remembered him as an Egyptian man paving his own road from a village in Upper Egypt to the Sorbonne in the first quarter of the 20th century.

For common Egyptians who watch TV series and read schoolbooks Hussein is a man who defeated poverty and blindness. For Arab intelligentsia he is the dean who took part in enlightening a whole nation despite being impaired from seeing the light.

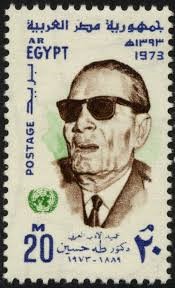

An Egyptian post stamp in honor of Taha Hussein few weeks after his death in 1973

0 Comments