COVID-19’s Narratives of (In)Vulnerability: Islam, Water, and Success in Small Indonesian Islands

While small Eastern Indonesian islands are often categorised for mediatic and administrative purposes as “vulnerable,” COVID-19 has hardly touched island spaces in North Sulawesi (Indonesia).

Much of regional attention comes to the islands to allocate development funds to “vulnerable groups”: a technocratic category stamped on minority Muslim communities in majority Christian North Sulawesi. But the Bajo islanders of Nain Island have often rebelled against being portrayed as “undeveloped,” “folkloric,” “vulnerable,” and “people on the outskirts.”

After centuries of avoiding a range of colonial administrations and of leadership in maritime affairs, Bajo histories of mobility and hybridity show nothing but connectivity, power, and reputation as holders of archipelagic wisdom. Islanders have often adopted and adapted the reductionist approaches of urban Sulawesians, regional governments, national government, environmental organisations, researchers, and international press in order to maintain complex local knowledge and heritage concealed and away from those who may pose a threat.

At the same time, the islanders of the Celebes, especially those with Muslim background, are often depicted as “the vulnerable other.” In North Sulawesi, as in many other regions in the world, religion seems to play a role in what becomes subjugated to hegemony, and by default defined as needing saving (i.e. purifying through the cloning of hegemonic systems of belief). But on the islands, Islam is far from a cause or a consequence of vulnerability.

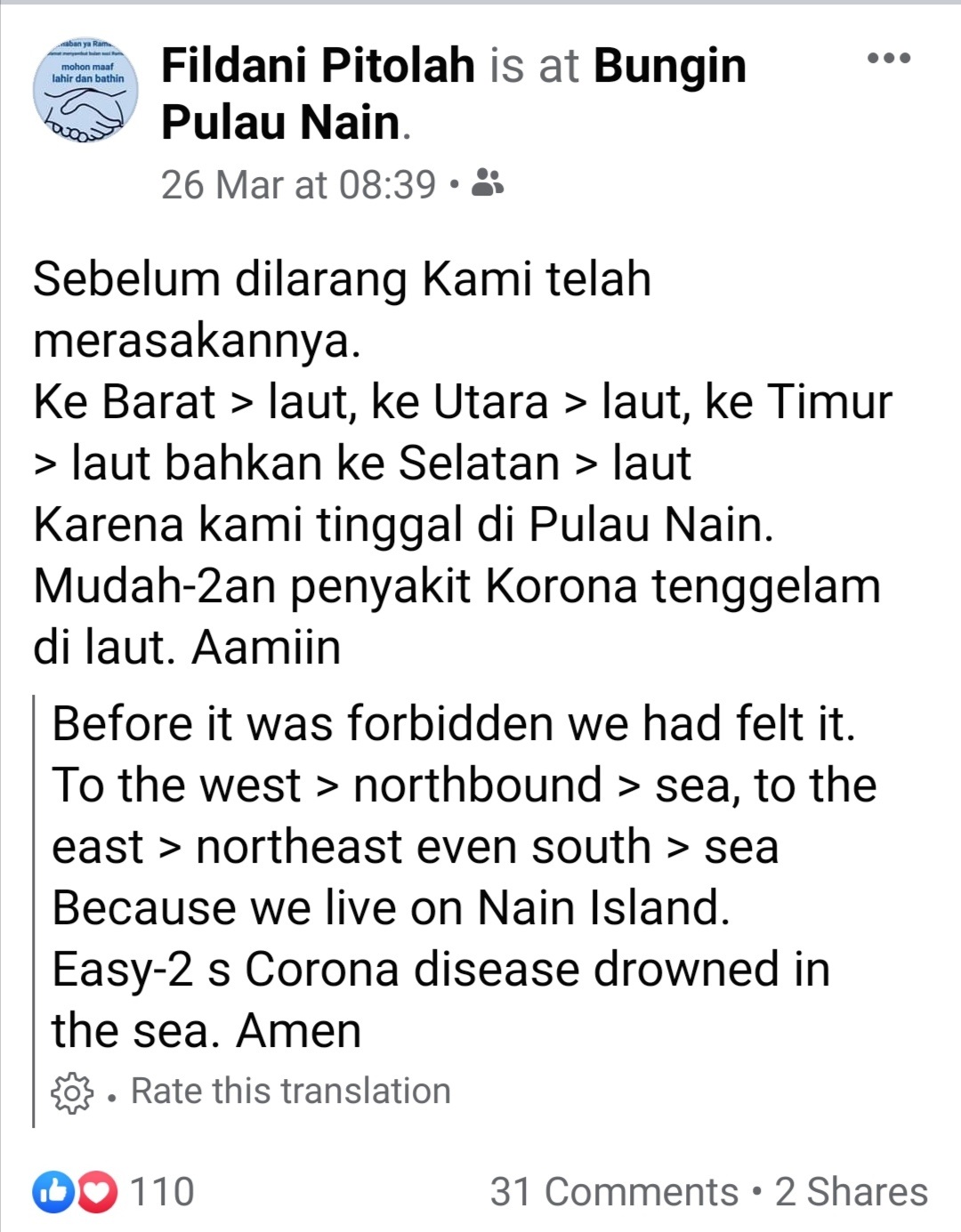

During the many conversations I had with Bapak Imam Nong throughout my years on the island, he pointed me in the right direction by stating that island Islam was not a choice, it was everywhere: in the water, the trees, the rocks, and as a resident of the island I too was Islam. Nain Island challenged a construction of religion that had been long institutionalised in the societies I come from: religion as a choice.

Island Islam was not a choice, not because it was imposed but because it was as natural as nature itself. Here, religion and environment were not generically divided concepts but mutually constitutive. The moral machinery of decontextualised critique could automatically situate Nain Bajo’s Islam into strict categorisations of orthodoxy or unorthodoxy. Such interpretative lenses are not relevant unless deconstructed and re-constructed in context’s own conceptualising mechanisms.

There is a certain islamophobic bias in today’s environmental sciences, humanities, and social sciences approaches. Scholars have critically engaged in discussing the mutually defining natures of local religion and environmental conceptualisation in the context of animistic religions, but the same intellectual space has rarely been allowed for Muslim contexts.

Islam has a deep historical continuity of engagement in the study, theorising, and conceptualising of nature (in theology, philosophy, and geometry, amongst others). Scholarship produced in Islamic contexts (from Al-Andalus to contemporary island Indonesia and beyond) has continuously engaged in conceptualising nature and natural science. The exclusive glorification of animistic religions and Buddhism as the go-to “religion of nature” by environmental scholars in political ecology, environmental anthropology, and area studies has often missed the role of Islam in blurring the boundaries between the natural and the human.

Such discussions are relevant as lenses to interpret how small islands have perceived, experienced, constructed, and reacted to the arrival of COVID-19. However, non-specialised media has often pandered to macro-narratives of politically inadequacy, remoteness, and overpopulation scaremongering. In doing so, the coverage of COVID-19 in archipelagic states falls short of the complexity of regional and transregional engagements. A tendency to homogenise Indonesia’s diversity obscures the success stories of small Eastern Indonesian islands and the prominent role of Indonesia’s civil society.

Success stories are often buried by sensationalism. Oversimplification and stereotyping move faster, read faster but, above all, they help further legitimise the (questioned) supremacy of more urbanised places and agendas. Some may feel these stories represent exceptions; some may need a sense of unity that is constructed upon presenting others as fragmented. Who knows? Whatever the reason, it is in the details of localised stories that success can be redefined again and again.

Meanwhile, the season of waves has kept the transit of those foreign to Nain Island away. This season’s dengue fever coincides with a new virus and once alarms of COVID-19’s contagion started to spread around Manado’s harbour and markets, Nain Island self-isolated and disappeared from the public eye. Here, self-isolation is not a newly romanticised possibility. On the islands, self-isolating has a historical continuity to a colonial past, and just like colonisers, COVID-19 travels by water and water shall decide its fate.

In times of macro-narratives of prevention, contagion, and healing, we, more than ever, need to lend an ear to the success stories of those who inhabit the frontiers of capitalism, those who are the “invisible” global actors of environmental healing. Places where water has successfully fought a new virus family: not by washing, cleaning, or purifying, but by once again keeping menace ashore.

0 Comments