Engaged anthropology in and about Yemen

What happens to anthropological research when the area in question is hit by war? Marina de Regt discusses the war in Yemen, its implications for her work, and how engaged anthropology strives to contribute to the world.

Roots of war

Since war broke out in Yemen, the country has become a no-go area, not only for researchers but even for humanitarian aid workers, who often have to wait long before they can enter the country. Since March 2015, the war has made tens of thousands of victims, more than 90 per cent of the population is in need of some form of humanitarian aid and the destruction of the infrastructure is beyond imagination. But what has led to this point?

First of all, this is not a religious war between Sunnis and Shi’ites. The war has its roots in long-standing political tensions and conflicts between various parties in Yemen and beyond. Secondly, the unprecedented explosion of violence is due to the involvement of Saudi Arabia, which is trying to increase its influence in the region. Third, the international community and especially the USA, France and the UK have great political and economic interests in supporting the Saudi Led Coalition, not least because of interests of the arms industry.

One of the main reasons that the situation in Yemen has exploded is the fact that Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was forced to step down in 2011 after 33 years of presidency, was allowed to stay in the country. He received amnesty for all his crimes against the Yemeni population during his presidency and especially during the Yemeni episode of Arab Spring, during which many peaceful demonstrators were killed. Behind the scenes Ali Abdullah Saleh sabotaged the National Dialogue in which the most important political parties and social movements were preparing a new constitution for Yemen. He struck a deal with the Houthis, a group he had been fighting against for years, and hoped that in this way he himself, or his son, could get back in power.

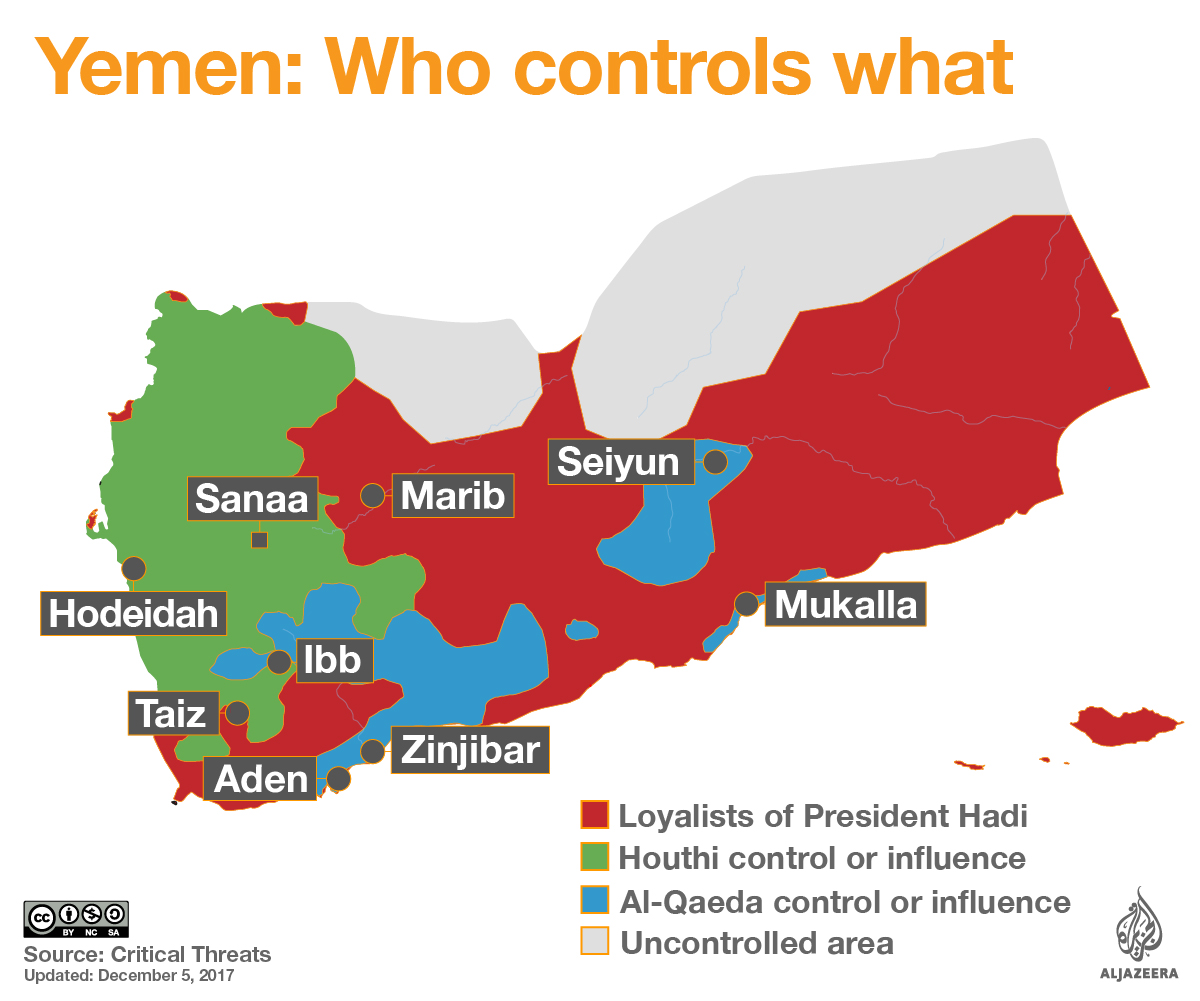

The Houthis are a minority group of Shi’ites who ruled Yemen during the Imamate (for centuries, Yemen by an Imam, who was both religious and political leader), and who felt marginalized politically and economically since that regime ended in 1962. They used the Arab Spring upheaval to increase their power, and could never have achieved their military successes without the support of Ali Abdullah Saleh. The alliance broke December 2017 when Ali Abdullah Saleh suddenly turned against the Houthis and said that he was willing to negotiate with Saudi Arabia to end the war. The fighting that subsequently broke out in Sana’a was unprecedented and led to the killing of Saleh on December 4. The end of Yemen’s war is now further away than ever, and the disastrous situation in the country has deteriorated to such an extent that some predict a Somali-like civil war which will continue for decades.

Research strategies

Here I come back to the question that lies heavy on anthropologists’ shoulders: how to do research when fieldwork is not possible? One of the strategies I used is to shift the geographical focus of my work from Yemen to a neighbouring country, namely to Ethiopia. I studied migrant domestic workers in Yemen, many of whom are Somali or Ethiopian. While I collected my main body of data in Yemen, mainly by interviewing migrant domestic workers, I also went to Ethiopia to interview family members about their daughter/sister/wife’s migration, and later to follow women who had returned from Yemen.

Another way to do research is to move back in time. Historically there have been close relations between Yemen and the Horn of Africa, with substantial migration/population movements from both sides of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. In the years that I lived in Yemen I met many people of mixed descent and I developed interest in their family histories. I interviewed Ethiopian women, who had migrated with their Yemeni husbands to Yemen in the 1960s and 1970s, and their daughters in order to analyze the impact of migration on gender, work and social status. Hence, by doing historical research it is possible to still contribute to knowledge and understanding about development in, around, and affecting Yemen, without having to travel to areas where one’s safety is constantly at risk.

And then, last but not least, I aim to do engaged anthropology, which in this case mainly entails the dissemination of research results to a wider audience. Speaking to the media is just one way of breaking the silence. Writing blogs, posting articles about Yemen on Facebook, and giving lectures to lay people are other ways in which I try to garner attention for Yemen. In our department we have made “engaged anthropology” one of our flagship maxims. We are convinced of the importance of an anthropological perspective on societal issues and believe that this knowledge can make a difference for our own societies and for the people we study.

Instead of generalizations, we shed light on the lives of individual people. We tell the story behind statistical numbers, which do not need to be wrong but, in our opinion, do not show the complete picture. In addition to that, we want to do research that benefits those people we study. We hope to improve their living conditions, support their struggles, assist them in their efforts to change their lives and share our insights with them, so that the knowledge that we generate contributes to a better world.

0 Comments