Hidden Treasures in Leiden University Library: Illustrations in Arabic Publications, 1960–1980

Leiden University library holdings include a substantial collection of Arabic fiction. Some Arabic publications from the 1960s and ’70s are richly illustrated by renowned artists. Judith Naeff highlights these hidden treasures

The Leiden University Library will be publishing an edited volume about its Middle East collection in 2023. It is well known that the collection includes many ancient manuscripts. Less well known are special publications of the modern and contemporary era. I had the honour to write a chapter on Arabic fiction book covers published between 1960 and 1980 and it was during my research for this chapter that I encountered several beautiful illustrations, not only on the books’ covers but also in the content.

The 1960s and ’70s were particularly fertile decades for Arab design and illustration: there was a sharp increase in numbers of publications and the dividing lines between graphic design and beaux-arts were not yet as distinct as they are today. Nowadays it is much less common for publishers to commission artists for cover art and illustrations.

Illustrations for Palestine: Mona Saudi, Dia al-Azzawi, and Nazir Nabaa

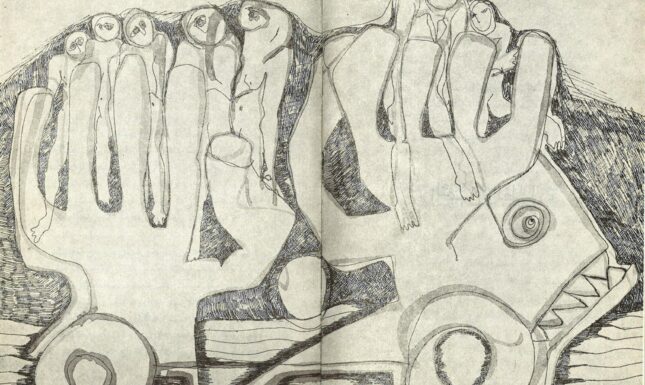

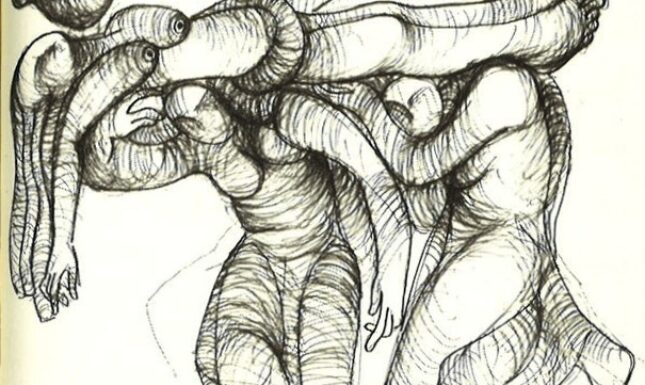

Absolute gems in the collection are the three volumes of the collected works of the Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani, richly illustrated by three renowned modern artists of the Arab world. The first volume contains Kanafani’s novels and is illustrated with art work by Mona Saudi (1945–2022), a Jordanian artist who sadly passed away earlier this year. Saudi fled her conservative family at age seventeen and moved to Beirut. There she sold her art until she had saved enough to go to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In the final year of her course, she took part in the massive student uprising of May 1968, which she saw as a turning point in her political and artistic work. Upon returning to Beirut, Saudi joined the thriving arts and publishing culture in that city as well as activist work. For example, she set up what would now be called an art therapy project with displaced Palestinian children. Saudi is most famous for her modernist sculptures. This craft also appears from her drawings, such as the two-page spread depicting a monstrous truck that doubles as two hands holding sagging figures (Fig. 1).

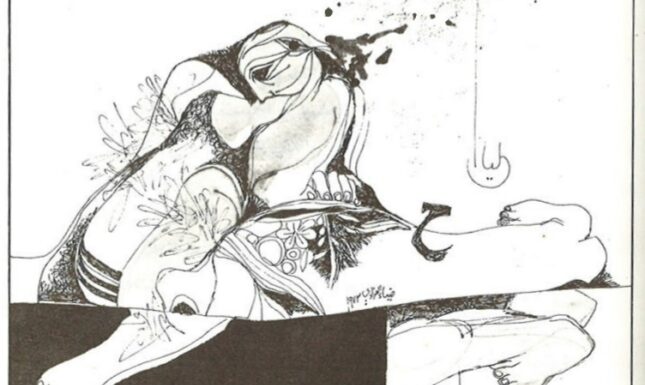

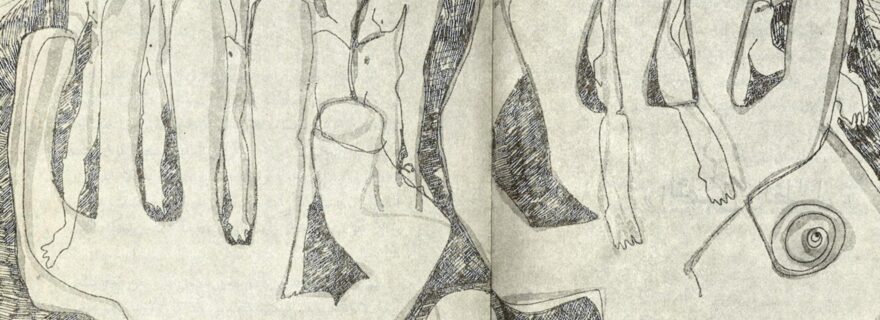

The second volume, of Kanafani's short stories, is illustrated by Dia al-Azzawi (b. 1939), an Iraqi graphic designer and artist. Al-Azzawi was commissioned to make these illustrations after Kanafani’s assassination in 1972. His drawings for ’Arḍ al-burtuqāl al-ḥazīn (The Land of Sad Oranges, 1973), narrating the exile of a Palestinian family from the perspective of a child, constitute a masterpiece. They consist of 33 ink-on-paper drawings, each forming a semi-abstract composition featuring body parts and spatial elements such as a dark square, suggesting an enclosed space, a bed frame or a flowing river. These compositions form an entangled whole, often off-centre in the frame, from which elements move outwards: splattering or dripping ink, flowing hair or reaching arms. Some drawings feature small decorative elements in the form of curls, flowers or letters (Fig. 3). In the copy in the library collection, the illustrations are scattered throughout the book, rather than being concentrated in the original story, thus losing some of the strength of the original collaboration between literary text and image.

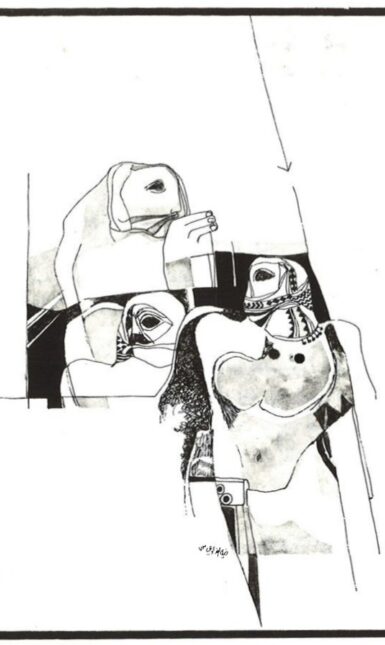

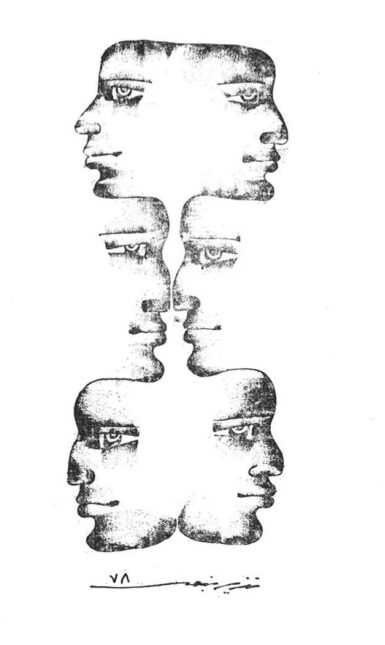

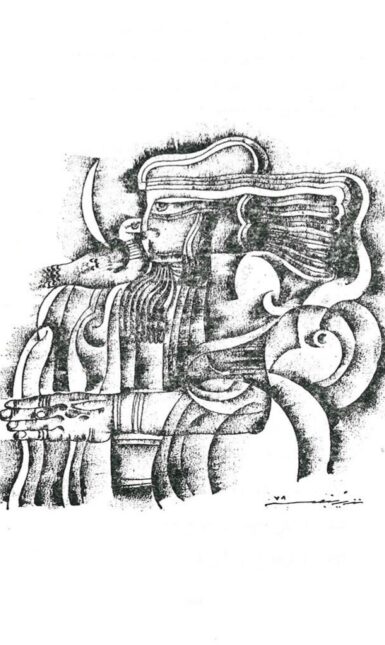

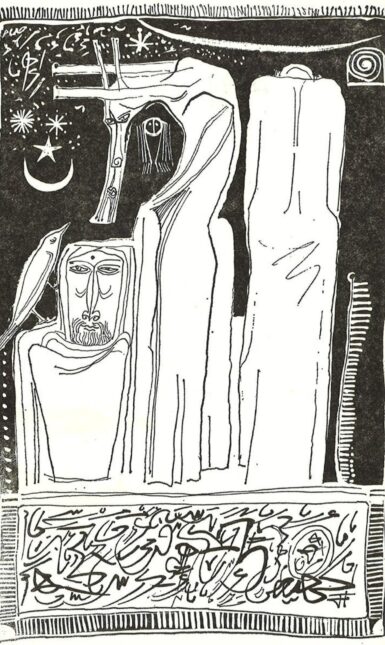

The third volume,

collecting Kanafani’s theatre plays, is illustrated by the Syrian

pioneer of modern art Nazir Nabaa (sometimes spelled Natheer). Nabaa was

trained in Cairo and Paris and is well known for his colourful

portraits of mythical women. Mostly inspired by Ishtar, the ancient

Mesopotamian goddess of fertility, the women are depicted in paradisical

gardens, adorned with jewellery, flowers and colourful scarves. Nabaa

was also highly productive in graphic design. His illustrations of

Kanafani’s plays seem to have been produced with a printing technique.

Most are portraits with elaborate entangled abstract forms and lines

(Fig. 6), but the volume also contains an intriguing figure of mirroring

faces reminiscent of a totem pole (Fig. 5).

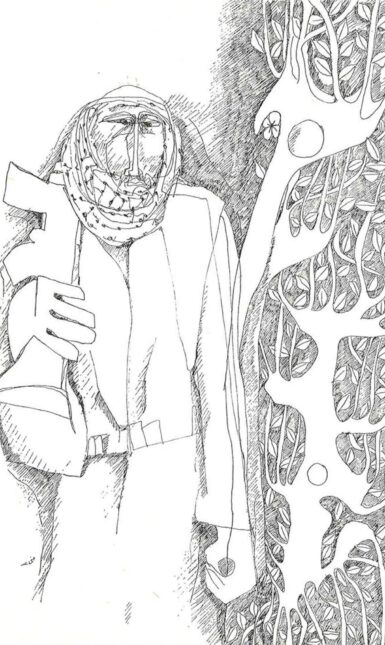

More broadly, the three artists contributed to the visual culture of the Palestinian struggle for liberation, by designing posters and illustrations for organizations such as the PLO and Palestinian Affairs magazine. In all three volumes, we see elements that have become iconic for the struggle for Palestinian liberation, such as the kufiyyeh, the characteristic Palestinian scarf, as well as orange and olive trees, doves, Kalashnikov rifles, and motherhood (Figs. 2, 4 and 6).

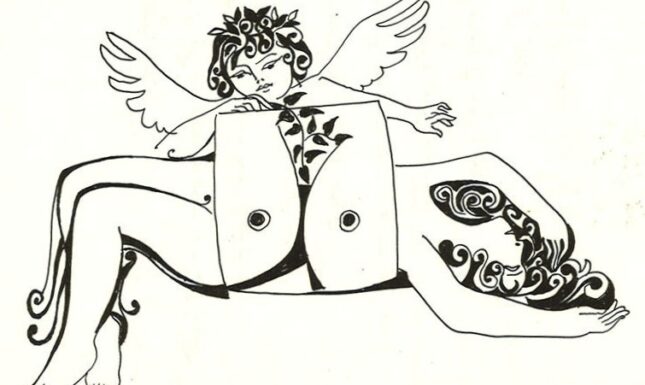

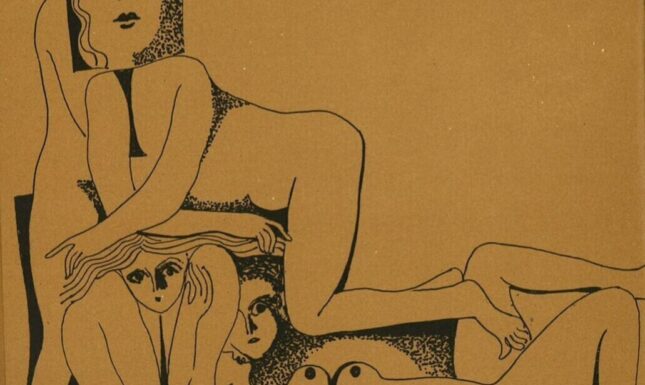

Illustrating Love Songs: Rakan Dabdoub

Rakan Dabdoub (1941–2017) is an artist who studied fine arts in Iraq and Italy and spent his entire career in Mosul, teaching drawing and free art at the Faculty of Engineering. Dabdoub is known for his oil paintings with a grainy texture, often depicting urban landscapes in cubist styles and soft colours. Like many postcolonial modernists of the twentieth century, he used motifs of ancient heritage and vernacular visual culture and folklore. Dabdoub illustrated a collection of love poems by the Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, titled ‘Uḥibbuki ‘uḥibbuki wa l-bāqiyya ta’ṭī (I Love You I Love You and the Rest Is to Come), which was published in Beirut in 1974, as well as the collection of prose poems by the Syriac Palestinian author Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Law‘at al-šams (Agony of the Sun), published in 1981. Some of the drawings are unabashedly erotic (Figs. 7 and 8). It was part of a wider discourse at the time that suggested that the depiction of female nudes by male artists would liberate women. But several illustrations of the volume are of a markedly different style, sketching figures with more depth. In one of these, two figures bow under the weight of a dead woman, while three pigeons have landed on her body (Fig. 9).

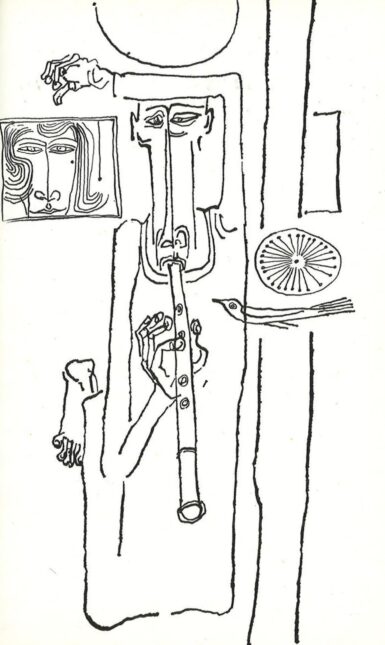

African-Arab Modernism: Ibrahim El-Salahi

Another treasure in the collection is the 1967 edition of the novella ‘Urs al-Zayn (Wedding of Zain), published alongside several short stories by the celebrated Sudanese author Tayeb Salih and illustrated by Ibrahim El-Salahi (b. 1930). El-Salahi’s paintings and drawings are characterized by modernist abstraction and use motifs from African and Arab vernacular culture. In recent years, international institutions such as Tate Modern and the Prince Claus Fund have hailed his work as a pioneering example of African and Arab modernism. His ink drawings for Wedding of Zain are more figurative than his autonomous work. They feature El-Salahi’s characteristic long faces reminiscent of African masks, natural elements, such as birds and palm trees, and vernacular visual culture such as the crescent, calligraphy and tapestry (Figs. 10 and 11).

Bonus: Faruq Al-Baqili

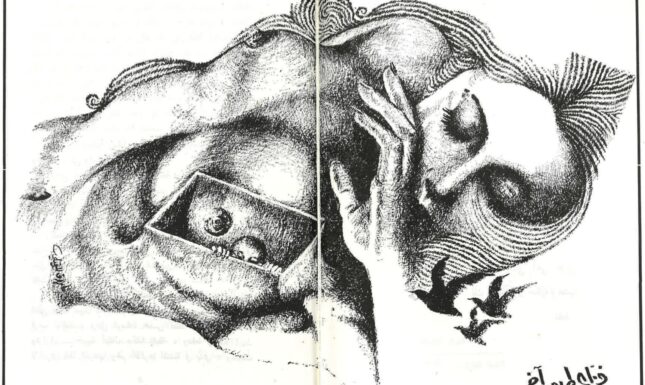

The final illustration highlighted in this blog does not quite fit among the others, as it was not produced by a famous artist. I found barely any information about Faruq Al-Baqili. He seems to have worked as a graphic designer and journalist or editor, probably in Beirut. He also wrote a book on the Iraqi poet Al-Jawahiri and was artistic director of the illustrated encyclopedia Bahjat al-ma’ārifa (The Joy of Knowledge). The image included here illustrates the short story Fazā‘ ṭuyūr ’ākhar (Another Scarecrow) by the Lebanese author Ghada Al-Samman and caught my attention because of the absurdist window through which a child peeks out from its mother’s heart (Fig. 12). The story is a heart-wrenching account of a barren woman who has lost all connection to her husband. She has unleashed her frustration by killing the cat’s kittens and is driven to despair when her maid has to deliver a baby, leading to a harrowing finale.

Note: The author has made every effort to obtain permission for reproduction of these illustrations in this blog, but was unable to reach some of the artists or their representatives. If you think that your copyrights have been infringed, please contact auteursrecht@library.leidenuniv.nl.

Further reading

Zeina Maasri, Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut's Global Sixties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Mona Saudi, “From Dreams to Achievements: A Jordanian Artist in the Era of 1968”. In: Lenssen Anneka, Rogers Sarah, Shabout Nada, eds., Modern Art in The Arab World: Primary Documents. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018, pp. 322–323.

Salah Hassan and Sarah Adams, eds., Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist. London: Tate, 2013.

Lina Hakim, Dia al-Azzawi Taking a Stand: Activism through Graphic Design. Amsterdam: Khatt Books, 2017.

The library holds various English translations of the works of Ghassan Kanafani, Tayeb Salih and Nizar Qabbani. A translation of Ghada Samman’s Another Scarecrow is included in An Arabian Mosaic: Short Stories by Arab Women Writers.

0 Comments