“Knowledge is Richness beyond Wealth”

(Elimu ni utajiri kuliko mali) An investigation into the private library of Mahmoud Mau inspires new research on Islamic intellectual history and the Swahili poetic production of coastal Kenya.

Langoni area, Lamu island, 350 km from Mombasa, Kenya: this is where Mahmoud Ahmed Abdulkadir—known by everyone as Ustadh Mahmoud Mau—was born and has lived ever since. Unless he is out distributing the Friday Bulletin to community members or delivering his Friday sermon at the Pwani mosque, Lamuans need only knock at his door to find him in his library. Ustadh Mau is the imam of the oldest mosque on Lamu. He is also a Swahili poet known throughout Kenya, an esteemed teacher, a follower of the Shafi‘i school, and a Salafist. The bakery that he inherited from his father—the son of a Hanafite originally from India—is now run by one of his sons. Mahmoud Mau leads a very humble existence, imbued with the social philanthropy and morals that are reflected (and voiced) in his modus operandi and vivendi.

I entered Mahmoud Mau’s library for the first time in 2014, when he became my primary informant as well as a fatherly figure to me. With his knowledge, I embarked on reading and deciphering nineteenth-century Swahili Islamic manuscript poems, which flourished and passed from one generation to the next in the Lamu archipelago, often considered the cradle of classical Swahili poetry. During our reading sessions, he never hesitated to take books from his shelves in order to clarify the interpretation or intertexual relations of the verses for me. While we were sitting there, people would drop by and ask for advice or commission poems. For this, he would turn not only to other books and pamphlets, but also to his own poetry in order to pass their lessons on to his community and open their minds.

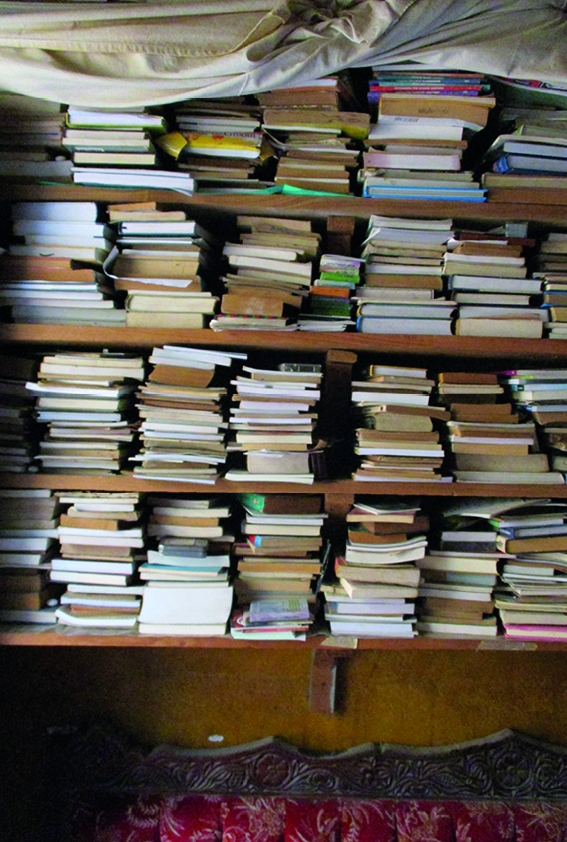

From these experiences, I gradually realized the value of Mahmoud Mau’s library as a living archive and its relevance for the literary-historic heritage of the island. The unique wealth of his books in Arabic, Swahili, and English is a treasure. As he says about his library in an interview, Mahmoud Mau’s joy lies in his books and this joy permeates his library: “Books are my joy; this is why I have set apart this space for myself, so that I can be alone with my books.”

In March 2018, in response to my question of whether knowledge reflects wealth, Mahmoud Mau explained that knowledge is richness beyond wealth (elimu ni utajiri kuliko mali), because whatever you take from knowledge, it only continues to grow, whereas when you use your wealth, it becomes less and less. Fearing that Muslims are losing their knowledge, he states, Tusione elimu ni ghali, “Let’s not think that knowledge is pricey!” By reciting a Qur’ānic verse, he reminds his audience that there is no better gift than the knowledge that parents impart to their children: “Let’s educate our children, so they may be properly educated.”

How has this been borne out by his own life experience? Ironically enough, it was under the influence of a close friend of his father, his teacher Ustadh Sayyid Hasan Badawy, that Mahmoud Mau was, as a school child, immersed in an environment that strongly believed that the secular school system was haram; this is why he never followed the traditional Kenyan school system. Since the arrival of Islam on the East African coast, Swahili pupils have received their formal education in Qur’anic schools (namely, the chuo and madrasa),where they become acquainted with Arabic, learn to recite the Qur’ān, imprint suras onto their memory and study how to compose qasidas, poetic odes.

Following this path, when he was just twelve years old, Mahmoud Mau started ordering books on his own from a bookshop in Cairo run by Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī and his brothers. This Cairene bookshop is indeed a well-known and still existing printing house located near Al-Azhar University. It has played an important role not only in Mahmoud Mau’s quest for knowledge, but also in the early printing history of other renowned Shafi‘i thinkers from East Africa, such as Aḥmad b. Sumayṭ from Zanzibar. His early works were printed there—a link that contributes to mapping both the earlier as well as the current Islamic book network across East Africa.

In total, Mahmoud Mau’s books number around one thousand now. Various Muslim authors from the past have forged his knowledge and inspired his thought including, for instance, Abbās Mahmūd al-‘Aqqād and his Muṭālaʻāt fī al-Kutub wa-al-ḥayāh (The Readings on the Books and the Lives). Mahmoud Mau so admired this writer that, at just 16 years old, he adopted ‘al-‘Aqqād’ as his own nickname.

On his shelves of Arabic books, the works of Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (imam Ghazali) and Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi can also be found. One book that was particularly illuminating for Mahmoud Mau is Muhammad al-Ghazali’s Laisa min al Islām (Not From Islam). While Sufism was very prominent on Lamu, this book had a deep impact on his religious thought. Mahmoud Mau was a follower of the Tariqa Alawiyya until 1968, but discovering al-Ghazali’s book changed his thought on Islamic doctrine. When he distanced himself from the Tariqa Alawiyya, some of his madrasa teachers were so disappointed that they began considering him a Wahhabi.

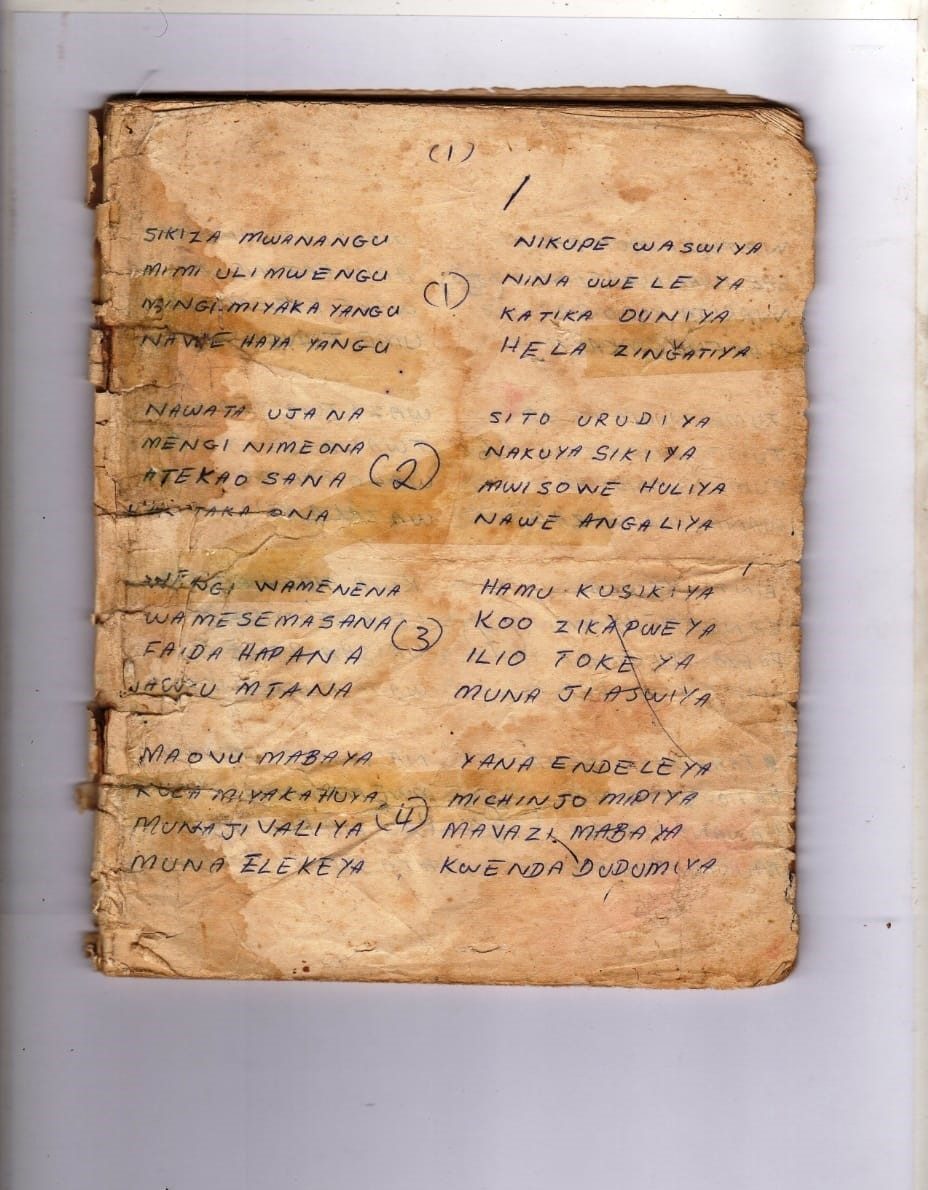

In explaining to me the relation between kusoma (to read) and kutunga (to compose), he specifies how reading enriches and enlarges your knowledge, and how necessary it is for a writer to read in order to be able to finely compose. It was for instance while reading the ʿAlī aṭ-Ṭanṭāwī’ booklet Ya Bintī (O My Daughter) that he was inspired to write his beautiful didactic poem Wasiya wa Mabanati (Advice to the Ladies), composed in utendi meter, which later became widespread via audio recordings distributed along the coast).

All in all, these Islamic books shaped Mahmoud Mau’s thinking and, in turn, inspired his writing and talks, illuminating the intellectual history and the Swahili poetic production of the East African coast. Investigating Mahmoud Mau’s private archive also sheds light on the history of Islamic ideas, which have travelled to remote corners where Islamic knowledge in African-language literature was, and continues to be, produced in abundance.

My sincere gratitude to Mahmoud Mau for sharing his memories, knowledge, and poetry with me.

A book that situates Mahmoud Mau’s oeuvre within the local context of Swahili Muslim knowledge production, co-edited by Clarissa Vierke (Bayreuth University) and myself, will appear in 2020.

0 Comments