Love, Friendship and Community in a Multicultural World

In the post Brexit world, it is crucial to revive stories from the past about cross-religious love and friendship. Wen-chin Ouyang takes us back to classical Arabic stories which show why reaching out to cultural others is an enriching experience.

Love and friendship are perhaps two of the most popular themes in storytelling worldwide. They are indispensable in any Hollywood film. A thriller is rarely enticing without a central love story that tugs at our heart and keeps us on the edge of our seats until our hero, with the help of good friends, untangles himself from a complicated web of deceit and reunites with his love.

Cross-species love and friendship

Love is the narrative motor even in Harry Potter. It also replaces a dysfunctional family. Harry Potter would be completely lost without his two friends, Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, who in fact give him a ‘true’ family after his parents die and leave him to be cared for by his abusive aunt, uncle and cousin.

Indeed, the passion which drives love and friendship is blind to colour, religion, class, and for that matter, any difference, and gives love and friendship their appetite for a world that is above and beyond the immediate family based in sameness. This is true of Harry Potter and a host of its precursors, such as The Lord of the Rings and The Golden Compass, and even truer of classical Arabic storytelling.

Contemporary rendition of classical themes

The kind of cross-species love and friendship we find between wizards and muggles in Harry Potter, between humans and elves in The Lord of the Rings, and between citizens of different parallel universes and humans and animals in The Golden Compass, is a contemporary rendition of classical themes across imperial, religious and class divides even at times of war. They are everywhere in medieval epics and romances around the Mediterranean.

When a prince and princess from different religious backgrounds fall in love, it often means victory for the prince. When a Muslim prince marries a Christian princess in Arabic epic, for example, he is sure to conquer her kingdom. A Christian king in a French romance achieves a similar feat by marrying a Muslim queen. This wish fulfilment impulse is perhaps the least interesting aspect of these stories.

More significant are the spaces opened up in the courtship between a Muslim prince and Christian princess for intercultural discourses, which reveal how intimately Muslims and Christian knew each other. This knowledge could only have come from continuous dialogue and living in close proximity to each other.

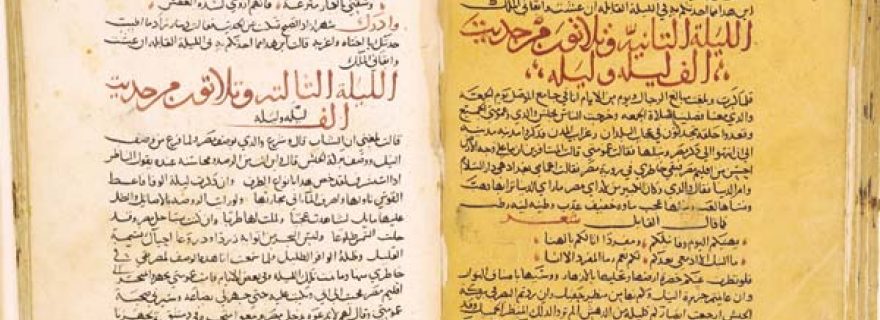

Al-Tanūkhī’s Al-faraj baʿd al-shidda

Two of my favourite are the uplifting captivity stories the tenth century al-Tanūkhī has saved for us in Al-faraj baʿd al-shidda (deliverance after hardship). The first goes like this. During his raids in Byzantine lands, Umayyad general Maslam b. ʿAbd al-Malik takes a Christian old man captive. When he orders the old man killed, the old man ask Maslama to let him go and he will bring back two Muslim captives in exchange. Maslama asks for a guarantor. The old man walks around the Muslim camps, identifies a young man and asks him. The young man agrees instinctively.

The old man goes away, returns the next day with two Muslim captives. He then asks permission to take the young man back to his fortress in order to thank him. At the fortress, the old man tells the young man that they are grandfather and grandson. He then describes his daughter to the young man who recognizes in the old man’s description his mother. He takes presents home to his mother, who recognizes her father, mother and sister from his son’s description. A bicultural family is born not to live in ignorance of its origins but to come face to face with and rejoice in its bicultural roots.

In the second story Qabāth tells ‘Abd al-Malik b. Marwān about his captivity in Christian lands. There he finds a kindred spirit in his captor, a well-educated multilingual Byzantine king, and they become friends. The Christian king too was at one time a captive in the hands of idolaters. As luck would have it, his captor, the king wanted a learned man to tutor his daughter in foreign languages. He volunteered. They fell in love, married, and he became king of both realms. He allows Qabāth to take part in a debate about Islam and Christianity at his court. The Grand Patriarch ends the debate by asking the king to free Qabāth and send him home. He will corrupt the Christian faith, the Grand Patriarch fears, if he stays. Words are clearly more effective than swords here.

Reaching out

These stories remind us of how easy and natural it should be for us to reach out to strangers and cultural others. Even people on two sides of religion are more alike than different. Muslims, like every people on earth, have been making families and forming friendships across cultures for centuries and their openness to the other allowed a multicultural empire to flourish under their rule. It seems to me vitally important to remind ourselves of what we have in common with them, not only our capacity to love and welcome the other but also how the other enriches us.

***

Wen-chin Ouyang is this fall’s LUCIS fellow. In November and December 2016, she delivers a series of five lectures on Reading Arabic Literature in a Global Context.

Upcoming lectures:

Thursday 1 December, 15.15 hrs: Silk an Spice in Literary Writings

Thursday 8 December, 15.15 hrs: Tammuz in Love

0 Comments