Mirroring the Other: The Feminist Narration of Islamic Glass Art in Works of Monir Farmanfarmaian

Delaram Hosseinioun discusses the mirror art of dame Monir Farmanfarmaian, through the lens of Judith Butler’s theories on feminine Otherness, highlighting the influence of the fourteenth-century Shāh Chérāgh Mosque on Farmanfarmaian’s work.

Introduction

Throughout millennia of Persian poetry and classical art, the female figure has been depicted as a comely daughter, a docile figure, or as an alluring muse. Yet this enchanting persona has little of the momentum necessary to announce her existence individually or outside of these frameworks.

The American philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler declares “Our capacity to reflect upon ourselves, to tell the truth about ourselves, is correspondingly limited by what the discourse, the regime, cannot allow into speakability” (Giving an Account of Oneself, 121). In this analysis, the Other stands as a metaphorical stigma inflicted upon women, deprived of the right to embrace their femininity. Thus the persona obliges the female artist to cope with cultural alienation. While Butler argues on how to negate the alterity of the Other, I extend this narrative and analyse Farmanfarmaian’s artwork as a platform for retrieving feminine identity.

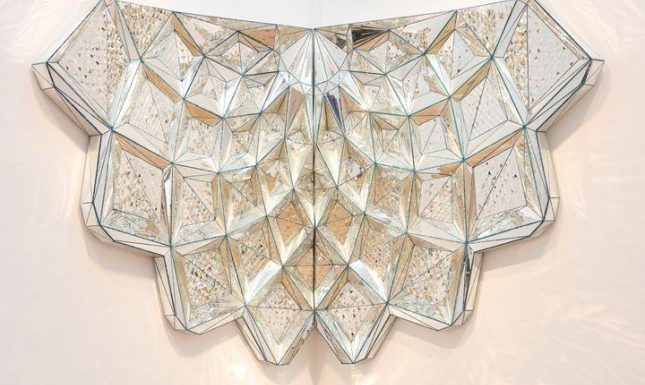

By adopting mirrors as her primary component, Farmanfarmaian not only reflects reality, but also alters women’s image as the object of the gaze. Instead of mirroring women as victims or damsels in distress, Farmanfarmaian rejoices the notion of womanhood and reunites her spectators through and beyond this Otherness.

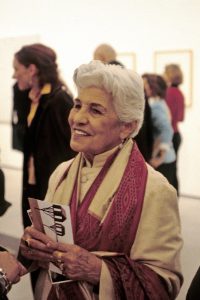

Monir Farmanfarmaian

The queen of dazzling mirrored mosaic works and glass paintings, Farmanfarmaian was raised by educated parents in the small, religious town of Qazvin in northwest Iran, where she was born in 1922. After studying at the University of Tehran at the Faculty of Fine Art, she moved to New York City in 1944 and studied at Cornell University. Absorbed into the American art scene of the time, she worked alongside artists like Jackson Pollock and, later, Andy Warhol. After twenty-six years of exile, in 1992 and 2004 she briefly returned to her country and exhibited her works. Her final visit was in 2017, two years before her death in April 2019.

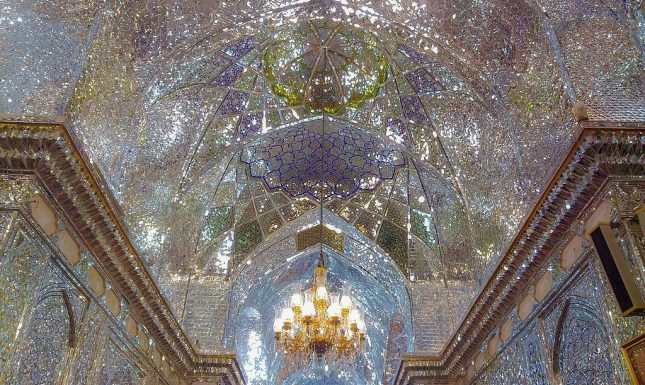

Inspired by the crystal tiles of the fourteenth-century shrine of Shāh Chérāgh (King of Light) located in Shiraz in southwest of Iran, Farmanfarmaian noted in her diary, “The very space seemed on fire, the lamps blazing in hundreds of thousands of reflections.” She wrote again about her experience in her memoir, A Mirror Garden:

“I imagined myself standing inside a many-faceted diamond and looking out at the movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance, in space, in sun. It was a universe unto itself, architecture transformed into performance, all movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance, in space, in prayer. It was so beautiful, so magnificent. I was crying like a baby.” (A Mirror Garden, 186)

The correlation of mysticism with numerology, Islamic geometry, and modern architecture frames the kaleidoscopic mirror mosaics of Monir Farmanfarmaian. As Farmanfarmaian notes, the epiphany in Shiraz left her “fired up with ideas,” inspiring her to delve into the realm of Persian philosophy.

Metaphoric numbers and geometrical shapes play a major role in Persian classic art. For example, as the symbol of eternity and heaven, octagons frame the mosaic decorations of shrines and sanctuaries. They can also be found in the majority of Farmanfarmaian’s mirror installations. Pursuing this imagery, she combines traditional Persian patterns and craftsmanship with abstract Western approaches.

Through a modern adaptation of Persian mosaics, Farmanfarmaian creates a unique hybrid image and invites the spectator to see herself through this merging of elements and perspectives. Subtly, her art also has a delicate yet solid feminine touch. Surpassing the cliche of the gender, each work urges the viewer to ponder the authentic image of Persian women.

Farmanfarmaian’s mirror art and Butler’s Other

Based on Butler's argument, gender and the roles imposed on the female gender are predetermined by a set of social contexts. It is only through narrating oneself that the woman can surpass barriers. In Undoing Gender, Butler argues, “One’s consciousness finds that it is lost, lost in the Other, that it has come outside itself, that it finds itself as the Other or, indeed, in the Other” (Undoing Gender, 240). Remarkably, when the spectator stands in front of Farmanfarmaian’s artwork, the fragmented mirrors lure their attention to the multiplicity of being and the plausibility of looking into one’s self in parallel aspects.

Established by Queen Tashi Khatun, through the centuries Shāh Chérāgh has maintained its fragile yet subtle charm and inspired its pilgrims. Based on the most iconic element associated with femininity, the mirror, Farmanfarmaian took its dazzling mirrors to break the cliché and confronted the restrictions upon women’s image and entity. She shows how femininity is entwined in Islamic art, each curve and tile reminiscent of feminine sensuality, reflecting the idealised charm or angelic aspect of women, yet not allowing them to be a part of its creation.

In order to reach such an understanding and to surpass this duality, it is essential to step outside of the frames imposed on women as the Other. Through mirroring the neglected aspect of femininity and celebrating their independent image, women can retrieve their identity and independent voice. Farmanfarmaian’s artwork manifests Butler’s notion of recognition and the importance of reunification with one’s self: “One is compelled and comported outside oneself; one finds that the only way to know oneself is through a mediation that takes place outside of oneself, exterior to oneself” (Giving an Account of Oneself, 28). By providing her spectator with such a platform Farmanfarmaian not only surpasses restrictions and reflects women's true image, but also exceeds Butler’s theories.

0 Comments