Modern Articulations of the Pilgrimage to Mecca

How do air travel and smartphones affect Muslims’ experience of the hajj? What is the impact of modern practices on the transformative experience as described in historical accounts? Marjo Buitelaar discusses continuities and changes, as part of the findings of her most recent project.

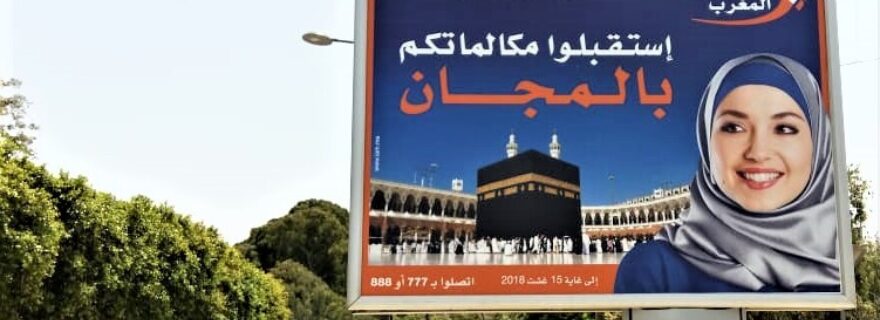

This blog presents some of the results of the NWO-funded research project “Modern Articulations of the Pilgrimage to Mecca” that is now in its finalizing stage. The project’s point of departure was that in today’s era of globalization, Muslims’ pilgrimage experiences are increasingly informed by a mix of different cultural discourses, resulting in new forms of religiosity and religious consumption patterns. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the hajj has undergone two periods of unprecedented growth; first as a result of the introduction of long-distance railways and oceangoing steamers and then, in the 1960s, the introduction of civilian air travel. These improved means of transportation and the global rise of new middle classes have brought the pilgrimage to Mecca within reach of large groups of Muslims beyond the Middle East. In the years just before the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, about 2,5 million pilgrims performed the hajj each year.

The explosive growth in pilgrimage to Mecca has produced new categories of pilgrims and led to the routinization and commodification of pilgrimage. Until a few decades ago, the meanings attributed to the hajj were strongly related to a conception of mobility that poses clear spatial and temporal boundaries. Most Muslims conceived of hajj performance as a once-in-a-lifetime event and a major rite of passage, marking a radical change in one’s status and lifestyle. Those who could afford to make the journey did so mostly at an advanced age, postponing the ”ultimate” religious duty in preparation for taking leave of one’s earthly existence. Today, the number of young and female pilgrims has increased significantly. Rather than (only) a preparation for death, hajj (also) takes on the character of a coming-of-age ritual that prepares one for adult life. Many European Muslims, for example, seek God’s blessings for their marriage by performing the hajj or voluntary ʿumra as a honeymoon or during the early years of wedlock. Such practices remain beyond the reach of less affluent Muslims and most citizens of Muslim majority countries where the quota system that was imposed to curb the influx of pilgrims seriously hampers pilgrimage performance.

Another trend among more affluent pilgrims is that they do not expect to visit Mecca just once but anticipate making the journey many times. A concomitant effect is that many pilgrims no longer consider it necessary or even possible to radically break with one’s past after having been cleansed of all sins through hajj performance. Rather, they hold the view that one should strive to lead an ethical lifestyle both before and after the pilgrimage, and that nobody is perfect; lapses are likely to occur and can be repaired by going on hajj once more.

Besides improved means of transportation, the smartphone is another technological innovation that has an enormous impact on people’s views and experiences of the hajj. It can safely be argued that the smartphone has become an integral part of the repertoire through which Mecca’s sacredness is experienced. Cherishing memories of one’s pilgrimage and keeping the experience alive by watching the photos one took with one’s smartphone stimulates reflection on how to anchor the transformative experience of the pilgrimage in one’s daily life, thus functioning as an act of ethical self-formation.

The smartphone has also influenced the mediation of the pilgrimage experience in another respect; it has affected the tradition of hajj storytelling through its affordance to create co-presence between pilgrims and those they left behind. A recurring storyline in historical Mecca travelogues and the oral accounts of contemporary older pilgrims concerns the anxiety and grief the narrators experienced when saying farewell to their loved ones as they departed for Mecca, only to find that once there, they were so absorbed by the sacred atmosphere that they miraculously forgot everything else and concentrated exclusively on the acts of devotion. Illustrating the extent to which the smartphone has become part of the habitus of younger Muslims, a Moroccan-Dutch female pilgrim who participated in the research project flipped this storyline around by explaining that it was precisely because her smartphone allowed her to stay in contact with her children that she could fully concentrate on her acts of worship rather than worry about home.

Obviously, there is also continuity between the centuries’ old tradition of hajj storytelling and modern pilgrimage accounts. For example, “being moved to tears”, when seeing the Kaʿba for the first time, and “feeling like a new born baby”, after having been cleansed of all sins, are recurring tropes in both the historical and contemporary accounts. They show the added value of comparing historical and contemporary accounts to study the pilgrimage to Mecca as a living tradition.

For more information on and publications by the project “Modern Articulations of the Pilgrimage to Mecca” (NWO grant 360-25-150), please visit the project’s website, www.nwo.nl/en/projects/360-25-150.

0 Comments