The Governor’s Orders: Part Two

Read the history behind the story published here last year on the arrival of a message from the governor of Egypt in an eighth-century Egyptian village.

In ‘The Governor’s Orders: Part One’, we looked at the world of eighth-century Egypt through the eyes of Shenoute, a village headman. The real protagonist of the story, and the object that triggered this exercise in historical imagination, was an actual document from Islamic Egypt. This post explores the contents of the real-life artefact and its importance among our sources on the Arab-Muslim rule of the province.

Scholars tend to treat the Arab-Muslim government of Egypt, centred in the capital Fustat, and the villages in the countryside which it governed as two separate worlds. In the world of Fustat, the Arab-Muslim governor and his fellow Arab-Muslim officials, judges, soldiers, and secretaries pronounced decisions, ran the country, and produced chancery documents, including tax demand notes, in Arabic and Greek. In the world of the countryside villages, farmers were slaving away in the sun in order to harvest enough crops to be able to pay their taxes. They solved their inheritance disputes with contracts in Coptic, the local language. Documents, such as the one under discussion, challenge this preconception and show how the Arab-Muslim government could be directly present in the villages of the countryside.

A message from the higher-ups…

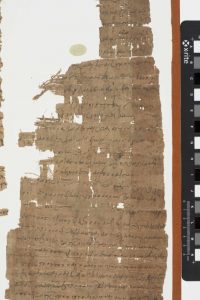

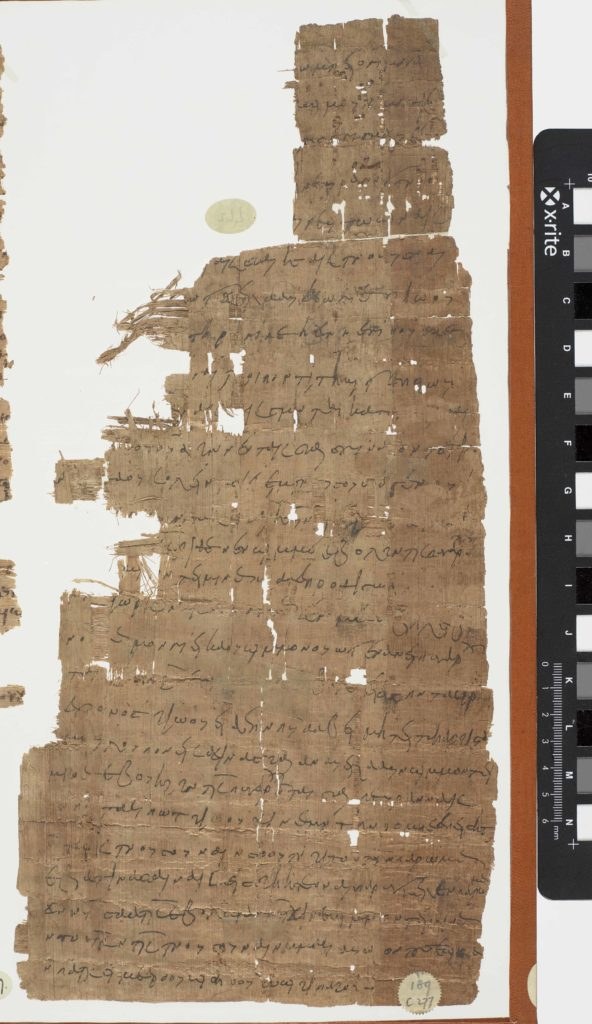

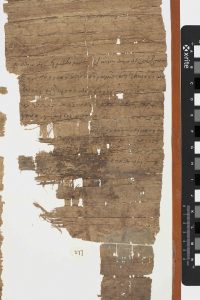

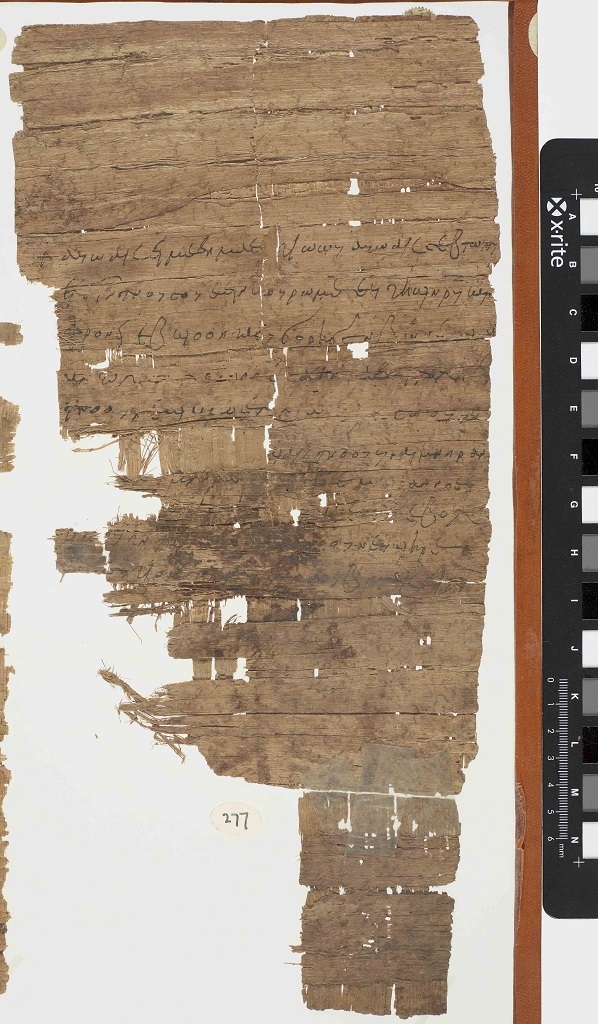

First, a bit of back story. Our document (P.Ryl.Copt. 277) is now kept in the Rylands Library in Manchester, UK, but was bought in 1898 in Cairo, together with many other Coptic documents. As a result, its provenance is unknown. It was edited in 1909 by the renowned Coptic papyrologist Walter Crum.

As you can tell from the photographs, the papyrus sheet was inscribed on both sides, but parts of it have been lost. The text reads like a letter, but there is no address with the names of the sender and addressee, so we do not know their names. It is clear, however, that the addressee was a pagarch (district administrator), as the sender writes several times about “your pagarchy”. The sender of the letter is clearly someone who has the authority to order and threaten a pagarch.

The letter contains instructions on what to do with “strangers” in the addressee’s district, people who had come to live there from other districts. Interestingly, the sender also seems to include people who had never spent time in the pagarchy to which they officially belonged and perhaps were born in the new district:

And I swear to you, by God, in truth, except for the sake of God, I will not allow a stranger, not one, among those from these pagarchies, whose names I have shown you, whether he has spent time in them or whether he has not done so… (P.Ryl.Copt. 277, ll. 16-19)

The authoritative position of the sender with respect to the addressee and his apparent competency to control the movements of people from several districts in the province strongly indicate that the receiver is a very high official belonging to the Arab-Muslim government of Egypt. It is possible that he held the highest office of governor, as we know from other documents that governors dealt with those issues. However, he could also have been one of the Arab-Muslim officials whom we see arresting fugitives in the papyri.

Further, when you receive my letter, see that every stranger of this sort, who is dwelling in your pagarchy, and whose names I wrote for you, … you send them to me forthwith, by my man, who will give my letter to you. See, also, I ordered my man not to return from you, until he receives the abovementioned strangers from you, and you send them to me with him. (P.Ryl.Copt. 277, ll. 20-26)

…in Coptic?

If this letter was issued in such a context, it is striking that it was written almost completely in Coptic. Arabic and Greek were the languages in which the higher officials of the Arab-Muslim government of Egypt communicated. In the story, Shenoute recalls how he was summoned to the office of the district administrator, to hear the recitation of a letter from the governor. There he receives a translation of the letter to take with him to the village. This is what I believe happened in the case of P.Ryl.Copt. 277, that it is a Coptic translation of a Greek or Arabic letter from a high official.

This interpretation is supported by evidence from other papyri. In two Greek letters on fugitives, the Umayyad governor of Egypt Qurra b. Sharīk tells district administrator Basilios to summon all village heads and policemen of his district, read the governor’s letter to them, and send them home with copies to read aloud publicly in their respective villages. While Qurra orders his Greek letter to be copied rather than translated, the relevant language for village consumption of documents would have been Coptic.

The linguistic expertise to make this kind of translation was available in the offices of the district administrators. They produced Coptic and bilingual Greek-Coptic documents, and in the case of Basilios, we know an Arabic scribe was at work in his office. By translating the official’s orders for the benefit of the inhabitants of the villages where the strangers were living now, the message of this high official of the Arab-Muslim government was brought straight into the lives of the villagers.

Merging worlds

We do not know whether this document was really read aloud to the inhabitants of a village – as I had Shenoute do in the story – or it was used to instruct the village officials, who would be responsible for rounding up the strangers and bringing them to the pagarch’s office so that they could be sent away. Either way, this document is a testament to how the world of Fustat and the world of the villages were integrated. We know that the new rulers of Egypt gradually increased their presence in the Egyptian countryside by installing Arab-Muslim officials, first alongside the local administrators, and later replacing them.. This document, a direct translation of the demands of the government for use in the villages, is one representation of this increasing presence of the new rulers in the Egyptian countryside.

I examine this document and its function in the administration and society extensively in my dissertation (in progress) on the protective interventions of local elites in early Islamic Egypt.

-- This blog was originally published on the Embedding Conquest website --

0 Comments