The Mantle of Roger II and the Fatimid Festival of Sacrifice

During the Festival of Sacrifice, Fatimid rulers publicly sacrificed a camel. Maribel Fierro discusses the political and religious significance of this ritual, and traces later versions under other dynasties. She argues a visual re-imagination even appears on the mantle of the Norman king of Sicily.

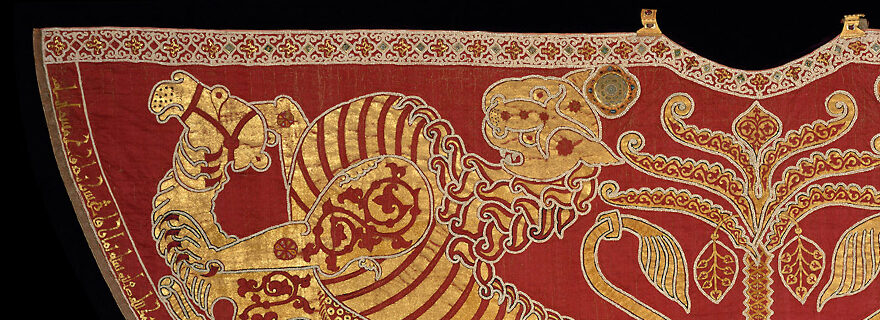

An intriguing scene adorns the lavish red silk mantle of the Norman king of Sicily, Roger II (r. 1130-1154). In gold embroidery, encrusted with pearls and precious stones, it depicts two lions killing two camels. An Arabic inscription on the mantle includes the year of manufacture: 528/1133-34. I propose to understand the mantle's iconography as the visual re-imagining within a Christian context of a powerful religious and political ritual innovated by the Fatimids.

The origins of this Fatimid ritual can be traced back to the would-be third Fatimid imam-caliph al-Manṣūr (r. 335/946-341/953), whose name was Ismāʽīl. He fought against a large-scale rebellion headed by a Khariji preacher known as “the Man of the Donkey.” While besieging him, the Festival of the Sacrifice (ʿĪd al-ʾAḍḥā) was held. Clad in a red outfit and a yellow turban with a long train, Ismāʽīl appeared in a festival square (muṣallā), set up specifically for the purpose, and slaughtered a she-camel with his own hands. Later imam-caliphs continued this powerful symbolic practice. No Fatimid texts explain why al-Manṣūr felt the need for this performance, nor why the animal sacrificed was a she-camel.

The Festival of Sacrifice commemorates Abraham’s (Ibrahim in Arabic) trial, when Allah commanded him to sacrifice his beloved son, but provided a substitute at the last moment. In the narrative recorded in Qur’ān 37:101-7, the ransom for his son is not specified; mention is only made of “a mighty sacrifice.” In some Fatimid texts, the best animal for sacrifice is described as a she-camel. Given their size, camels could seem to correspond better to the Qurʼānic “mighty sacrifice” than other animals, but there are also other reasons why camels were especially fitting.

ʽAbd al-Muṭṭalib, the Prophet's grandfather, had vowed to sacrifice one of his sons (the Prophet's father) who was eventually ransomed by one hundred camels. Camels were the animals sacrificed by the Prophet Muḥammad both at al-Ḥudaybiyya and the Farewell Pilgrimage, on this occasion helped by ʽAlī b. Abī Ṭālib – the ancestors claimed by the Fatimid imam-caliphs. Moreover, camels were linked to the Arabs and thus to Ismāʽīl, the son of Ibrahim, who was their ancestor, as opposed to the Jews who descended from his other son Isḥāq.

Perhaps when the Fatimid Ismāʽīl publicly performed the sacrifice of a she-camel for the first time he wanted to emphasize that Ismāʽīl and not Isḥāq was Ibrahim’s son chosen for sacrifice. This was a debated issue in Islam and may have acquired special saliency at the time, as the enemies of the Fatimids accused them of not really being descendants of the Prophet through his daughter Fatima and his cousin ʽAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, but rather descendants of a Jew.

Another possible reason for the election of the animal may have had to do with a special type of camel, the sā’iba. In pre-Islamic times, sā’iba referred to an unfettered camel that roamed freely and was considered untouchable, a belief abolished with the advent of Islam. In North African political culture, the expression “land of al-sība (=sā’iba)” or bilad al-siba became a metaphor for the untamed and un-subdued, signifying the territory where dissidence, lawlessness, ungovernability, statelessness, chaos, and civil war reigned. I propose that the sacrifice of a she-camel was a way to symbolize the taming of the Khariji rebel who had threatened Fatimid rule: in the same way that the she-camel was slaughtered by the imam-caliph, he would subdue his enemies. Ritual slaughter in Ismaʽili taʼwīl (esoteric interpretation of the Qur’ān) stands for the oath of allegiance.

After the Fatimids, the Safavids (907/1501-1135/1722) of Iran were the other dynasty whose rulers publicly sacrificed she-camels. The ritual continued under the Qajars (1794-1925), until Reza Shah (1925-1935) put an end to it in 1933. The practice may have started under the third Safavid Shah ʽAbbās I (r. 996/1588-1038/1629), or at least this is when European travellers to Iran first described it. For three days, a she-camel decorated with flowers was paraded through Isfahan in processions, protected by men armed with big sticks. On the day of the Festival of Sacrifice, it was solemnly brought to the place of sacrifice, two miles beyond the city walls, and made to lie down. The king or his delegate, mounted on a horse, would proceed to spear it between the ribs with a lance.

Muslim sources for the Safavid period say nothing about this practice, to which some Twelver Shiʽis mullahs objected because, according to the law, the camel had to be slain standing and not lying on the ground. The Ismaʽili communities living under Safavid rule may have been the channel through which the Fatimid practice was adopted and adapted by the Safavids.

In North Africa, where the Fatimid practice started, the public killing by the ruler of a sacrificial animal is also attested among some of the post-Almohad dynasties (13th-15th centuries). The practice was later adopted by the ʽAlawi rulers of Morocco, who still perform it to this day. But in their cases the sacrificial animal is a ram.

The politically and religiously significant Sacrifice Ritual innovated by the Fatimids appears to be a clear precedent of the post-Almohad, Safavid, and ʽAlawi practices. Curiously, this has been considered in neither extant sources nor later studies. This oversight has to be related to two main factors. Firstly, the comparative study of political ceremonies and religious rituals in the Islamic world is still under-developed. Secondly, the perception of the Ismaʽilis as dangerous and radical heretics still looms large in the historiography of Islam. Thus, there seems to be reluctance to admit the possibility of Ismaʽili/Fatimid influences in the religious and political culture developed by other religious groups and dynasties, even though there is no scarcity of examples.

If this is so within the territory of Islam, a possible Fatimid influence in the political (or perhaps also religious?) iconography of the Norman Christian king is bound to be controversial, even against the background of the well-attested close relations between Normans and Fatimids. As noted above, the mantle of Roger II was manufactured in 528/1133-34. This was after Roger II's coronation as king of Sicily, when he was facing rebellions in southern Italy, as well attacks from both the Holy Roman Emperor, Lothair III, and Pope Innocent II. This was also a time when he was using Muslim troops to counteract his Christian enemies and had to control his own Muslim subjects. The Fatimid ritual signalled the power of the imam-caliph to subdue the rebels who challenged his rule, and Roger II – who ruled both Christians and Muslims – was also in need to send such a message. The mantle with the two lions killing two camels visually conveyed the same symbolic meaning as the Fatimid Festival of Sacrifice, to his supporters and enemies.

0 Comments