United in Life, Divided in Death: Religion and Gender at the End of the Lifecycle in Egypt

Islamic family law studies often focus on marriage and divorce, but what about death? What are the rituals and procedures at the end of the lifecycle, and what role do religion and gender play? Nadia Sonneveld searched for preliminary answers during a recent visit to Cairo.

I have been strolling the City of the Dead for less than an hour, and yet I have already counted four funeral processions. In this part of historic Cairo, tomb enclosures and mausoleums are everywhere, forming a vast series of necropolises and cemeteries. At the first funeral, I see people praying in front of the tomb enclosure (hawsh) where the body lying in the casket will soon be buried. Men are standing in front of the building, the women behind them. At the funeral procession a few blocks away, men are carrying the coffin inside the tomb enclosure. Funeral attendees follow in their footsteps, including a middle-aged man supporting an elderly woman with walking difficulties. During interviews with Middle Eastern Muslims living in the Netherlands, the issue of women attending funeral prayers and burials is often controversial. On that particular Wednesday in Islamic Cairo, Muslim women praying and attending burials are a common sight, however.

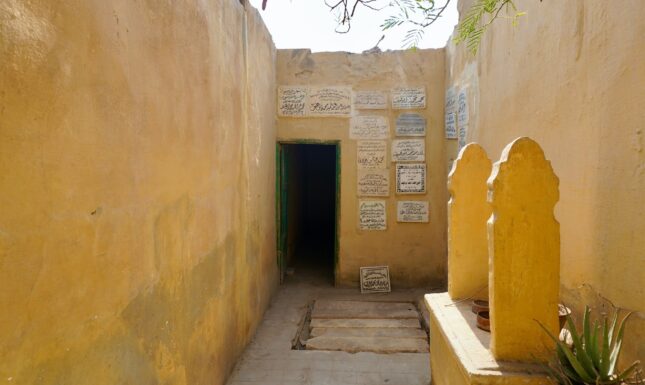

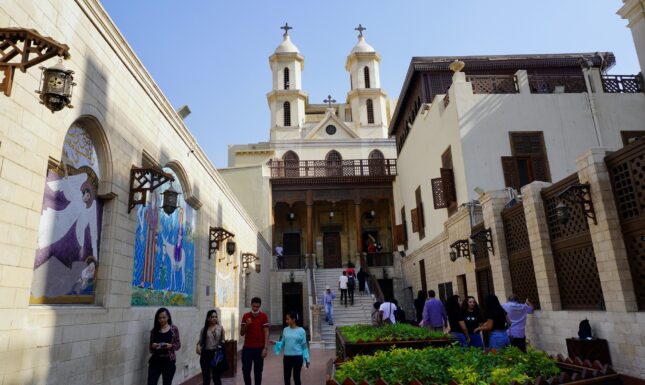

A few days later, I visit a Coptic cemetery near Cairo’s famous Hanging Church. Dotted with little statues of angels, doves, and crosses, the cemetery has a different feel to it than the Muslim ones I visited that lack figurative representation. Here women pray and attend burials too. Seemingly, gender segregation does not play a role when it comes to burial practices in Egypt, and the same applies to religion; I know from years of research and friendships in Egypt that Muslims attend the burial of Christians and vice versa. But here in Cairo, I learn about a story unfolding under the ground, one in which segregation by gender and religion does occasionally play a role.

While interfaith marriages in Egypt are allowed, they are strictly regulated: a Muslim man is allowed to marry a Christian (or Jewish) woman, but a Muslim woman is not allowed to marry a non-Muslim man. Hence, a Christian man who wants to marry a Muslim woman must convert to Islam. After his first marriage had become dysfunctional, a Christian respondent had converted to Islam to marry a Muslim woman. She had become his second wife; given the stigma of Christian divorce, he had not divorced his first wife and had even continued providing for her. After he died, he was buried in the family grave at a Coptic cemetery. According to a relative, this was only possible because he had formally converted back to Christianity after the death of his second wife. Graveyard managers, the relative said, do not allow interfaith burial and always verify the official religious identity of the deceased as mentioned on their ID and the burial permit (tasrih al-dafn).

There are no formal regulations that prohibit interfaith burial of, for example, spouses side by side, but it simply does not happen a lawyer told me. In Egypt, he said, you have cemeteries for Muslims and cemeteries for Christians. Each year, the governors of Egypt’s different provinces allocate space for new cemeteries, thereby indicating the percentage of land that is reserved for Muslims and for Christians.

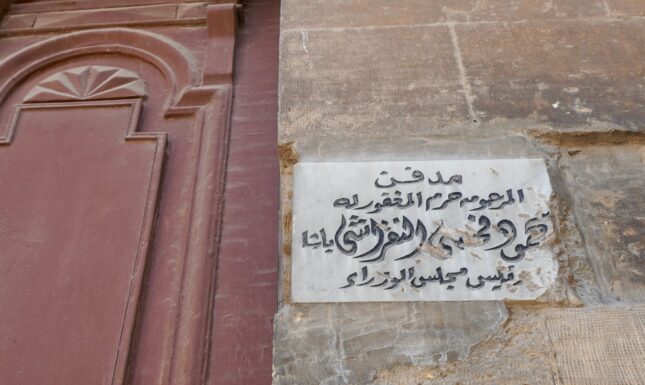

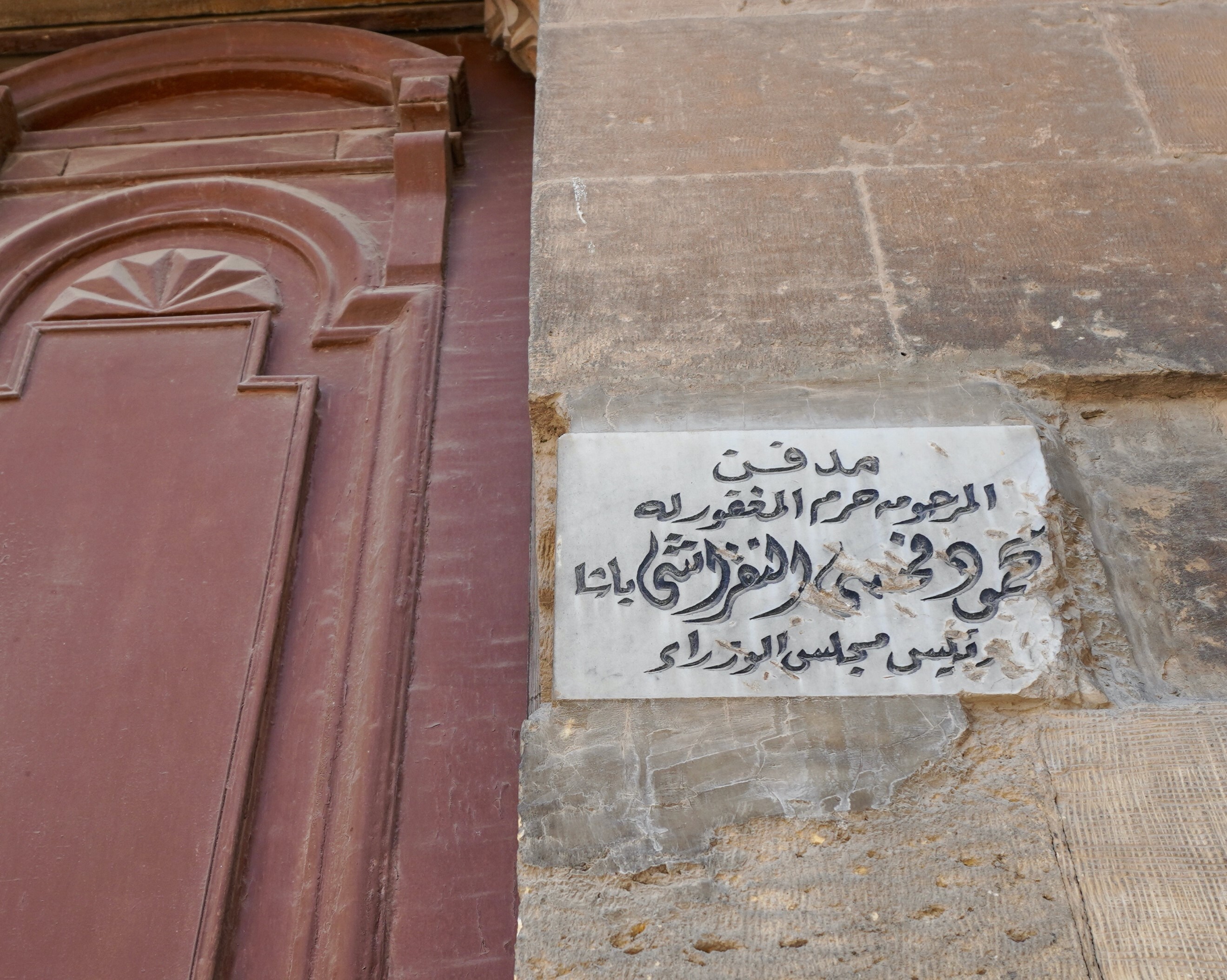

Even couples belonging to the same religion or denomination do not always spend eternity side by side. For example, at the Coptic graveyard near the Hanging Church, plaques abound denoting the name of the male head of household, even when he is buried somewhere else, in the village of origin, for example. In the City of the Dead, a huge tomb enclosure was built for the wife of former prime minister Mahmud Fahmy al-Nuqrashy Pasha (1888-1948) while the prime minister himself was laid to rest in a mausoleum in Abbasiya. But even when Muslim couples are interred in the same graveyard, men are buried on one side and women on the other. When the graveyard is full, the bones are collected and stored in separate corners of the enclosure.

However small their number may be, there are also Egyptians who are not religious or who have religious doubts. They formally belong to one of the recognised religions, and, as such, a graveyard manager will not object to burial in the graveyard, but family members who disapprove of the presence of a nonbeliever in the family grave may. To avoid the risk of becoming alienated in death, nonbelievers sometimes buy an individual grave or they build a new family grave for themselves and their nuclear family members.

Death is part of family life, in the same way marriage and divorce are. Family law studies would do well paying more attention to rituals and procedures at the end of the lifecycle: after all, they offer a window into people’s understanding of the social order and their place within it.

This blog presents preliminary findings that relate to the ongoing NWO-funded Vidi research project “Living on the Other Side: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Migration and Family Law in Morocco.” The project asks how migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East deal with formal and informal procedures pertaining to family law matters, such as marriage, divorce, and death. For more information, see https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/research/research-projects/law/migration-and-family-law-in-morocco

0 Comments