An Egyptologist’s Breakdown of “The Prince of Egypt” (1998)

The 1998 animated film, never released in Egypt, was criticised for misrepresenting ancient Egypt. A closer look reveals that, in many ways, it is clearly inspired by Egyptian archaeology.

Last month, London saw the premiere of “The Prince of Egypt,” a musical based on the eponymous animated film that came out in 1998. The DreamWorks picture tells the story of the Book of Exodus, and depicts Moses as an Egyptian prince who discovers his Hebrew roots, flees the palace and returns to deliver the enslaved Hebrews to the promised land. The story is almost entirely set in ancient Egypt, but the film was never released in contemporary Egypt. The Egyptian government banned it for its portrayal of a prophet, often considered forbidden in Islam. But perhaps more significantly, the movie outraged several Egyptians who believed it misrepresented ancient Egyptian history. Similar concerns were the reason for the Egyptian ban of the 2014 motion picture “Exodus.” Nonetheless, “The Prince of Egypt” is, in many ways, demonstrably inspired by Egyptian material culture. Here’s an Egyptologist’s breakdown of selected aspects of the film.

Royalty

Sure enough, the film takes liberties with biblical and pharaonic history. In the Book of Exodus, the pharaoh is never mentioned by name, but the film identifies him as the historical king Ramesses II. The film thus implicitly dates the story to around 1250 BCE.

Moses and Ramesses are seen growing up during the reign of Ramesses´ father, king Seti I. Seti I´s facial features even bear some resemblance to the king’s actual appearance, preserved in his mummified body.

Slave labour

Perhaps most contested is the depiction of the Hebrew slaves. There is archaeological evidence for “Canaanites” or “Asiatics” (Levantines) in Egypt, but not much is known about them and they were certainly not all slaves in the modern sense of the word. Still, various forms of corvée, forced labour, and slavery existed in ancient Egypt. To underscore the theme of unbearable slave labour, the film often grossly exaggerates the dimensions of Egyptian statues and buildings.

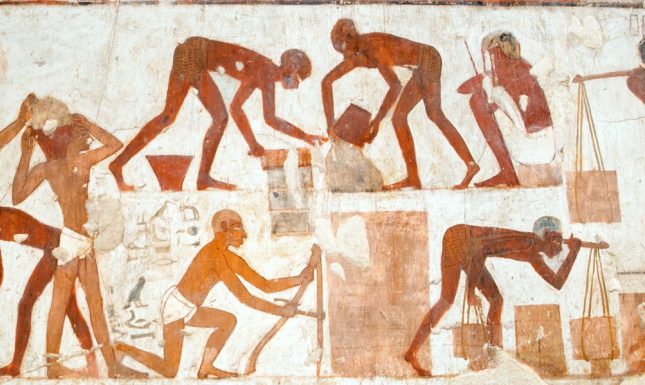

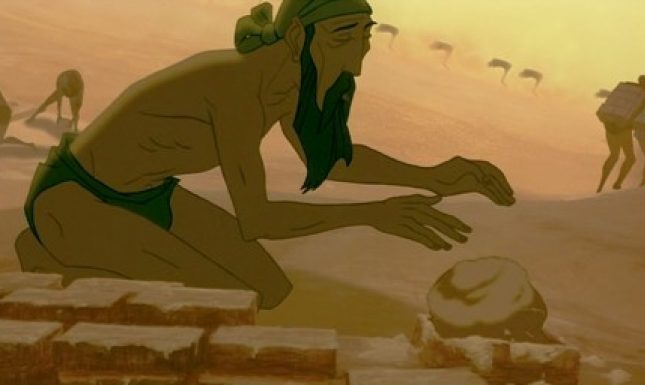

Construction

Building techniques in the film are based on archaeological evidence. Slaves are producing mudbrick and carry loads of building material, while overseers strike them with whips. A very similar sequence is depicted in the tomb of Rekhmire, in which workmen use baskets instead of sacks and overseers have sticks rather than whips.

Several examples of Aaron´s chisel and hammer have been excavated.

Writing

Temple and palace walls are inscribed with authentic Egyptian hieroglyphs. Some sign groups even contain actual words, but generally they do not form sentences. Still, early in the story, during the reign of Seti, walls are inscribed with his royal names.

Later, when Moses returns to the palace, it is inscribed with the names of Ramesses who has succeeded his father.

Memphis

Several scenes are clearly set in the royal palace in Memphis, a large city near the pyramids of Giza.

The Egyptians called the city the "White wall," which features in a view of the landscape.

The film’s design is wrong in showing colossal statues facing each other. These would always be directed towards the viewer. More importantly, during the reign of Ramesses II, statues of gods would mostly stand inside sacred chapels of temple, not outside in temple courts.

However, towards the end of the film, the departing Hebrews walk by a collapsed statue inspired by an actual colossal statue of Ramesses II from Memphis.

Interestingly, a wall in the palace depicts king Akhenaten, identifiable by the hieroglyphic inscriptions. In fact, the relief is a copy of a stela of Akhenaten. This is probably a nod to the monotheistic revolution brought about by this king, who abandoned the traditional gods in favour of a single god – a theme explored in the film. Ironically, many of Akhenaten’s reliefs were destroyed after his reign when the Egyptian gods were reintroduced, and Seti would have never tolerated this image of the rebel king.

Dress

The film depicts Egyptians wearing realistic white linen garments.

These are contrasted with the colourful garbs of the Hebrews, perhaps modelled after Egyptian depictions of Canaanites who may have worn dyed woollen clothing.

Moses wears a wig over his real hair, as most well-to-do Egyptians would have.

The insides of his sandals, based on those of Tutankhamun, depict the traditional enemies of Egypt.

The Egyptian queen wears the typical vulture headdress.

Like prince Ramesses, Egyptian children and adult princes would be coifed with a side lock.

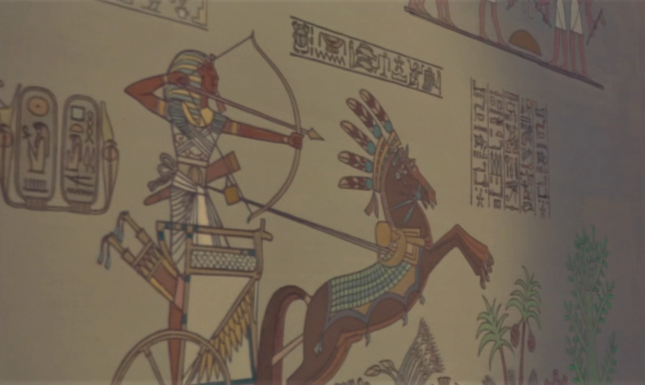

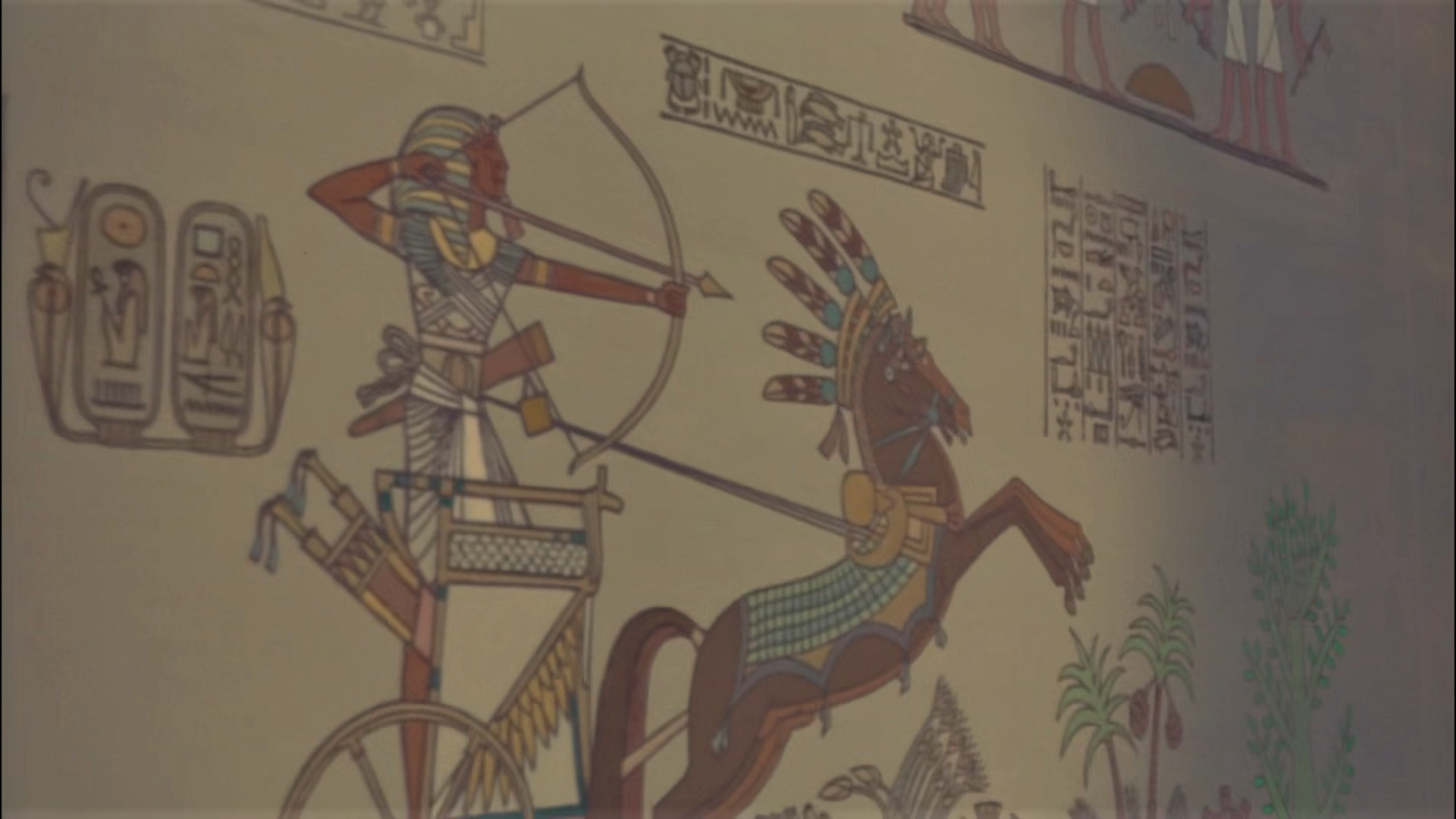

Finally, when Ramesses and his army chase after the Hebrews, he is wearing the blue crown and an armour of falcon´s wings. This outfit is clearly lifted from a relief in the temple of Ramesses II at Beit el-Wali that depicts his Nubian campaign.

Daily life

Ramesses and Moses are seen racing horse chariots. These are spot on and must have been designed after the chariot from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

They speed past some men playing a board game that Egyptologists have dubbed “Hounds and Jackals.”

Less convincing are the depictions of pillows seen on beds. While the Egyptians must have had pillows, evidence suggests they slept on beds with a head rest.

Moses’ lamp stand, on the other hand, has parallels in Egyptian archaeology.

Love for the culture

Whether DreamWorks deliberately wanted to mislead audiences about Egyptian history is a different debate. From an Egyptologist’s point of view, however, it transpires that the creators had a real love for the material culture of ancient Egypt. Their recreation of life during the time of Ramesses is more often accurate than not. That is much more than can be said of movies such as “Gods of Egypt” (2016) and “The Mummy” (2017). They are every Egyptologist’s worst nightmare in terms of historical accuracy, yet were released in Egypt without any fuss. Much more historical scholarship went into the making of “The Prince of Egypt,” and it deserves to be revisited.

3 Comments

I just got the dvd for Christmas and must say: I'm so grateful for this post. As an aspiring ancient historian, this was a joy to read, and I really appreciate the many aspects of the film's portrayal of Ancient Egypt that were shown. I enjoyed learning from it, wishing you all the best,

Sofia

Dear Jess,

Thank you for reading my contribution and for your comment. I think your interpretation of the dimensions of statuary and architecture and the depiction of Akhenaten make sense. You may well be right. I tried to discuss these and other aspects of the film mostly from an archaeological perspective - not to critique the film and to point out 'mistakes' - but to highlight what we know about ancient Egypt from the archaeological record.

All best,

Daniel

I'm really glad you took the time to analyze and compare this film to everything known about Ancient Egypt.

You had mentioned that the statues and structures were massive and oversized, and I wanted to say that they may very well be metaphors to the grandiosity of it all (especially when in the same frame as the Hebrew slave quarters), as well as how it must have felt to those that actually built them.

I also want to mention that maybe the depiction of Akhenaten was shown to foreshadow Moses' acceptance of the single Hebrew God, paying special attention to how it comes into frame. (This also happens immediately after he stumbled upon his Hebrew siblings, who told him everything, and then begins to have an identity crisis.) The creators were geniuses in their use of subtle imagery, much of it easily missed unless you're actively looking for it!

As much as I adore this film, I don't believe anything is above valid and constructive criticism. I'm curious for your thoughts!

I wish you all the best,

Jess