Dutch Fire Diplomacy in Early Modern Istanbul

Like in any other metropole of the early modern world, city fires formed an imminent danger in Ottoman Istanbul. The diplomatic representatives of the Netherlands reported dozens of these fire incidents from their Dutch Palace in the Galata district, not only as spectators but also as victims.

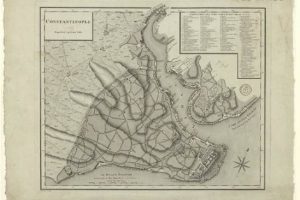

Between 1750 and 1850, Greater Istanbul (Galata and Üsküdar included) suffered from more than a hundred major conflagrations that paralysed life in the city. A quarter of these fires were reported in the Galata district where also a cluster of European embassy buildings was settled.

In their monthly reports, the ambassadors could not stress enough the harmfulness of fire incidents.

| “Hoezeer men by zulke gelegentheeden altoos wel eenige schaede heeft, leeven wy hier in een land, daer men egter in vergelyking van het geen men in een uur tyds verliezen kan, om dier gelyke klyne schaedens niet eens mag denken, dewyl men dag en nagt jaer in jaer uit altoos gereed moet staen, om met pak en zak op te breeken, en alles best mooglyk te bergen.” | |

| “Although we always suffer some damage on such occasions, we live here in a country in which we compared to what we can lose in an hour, we even cannot think about such small damages, while at the same time, we have to stand ready, day and night, year after year, to act quickly, using every means available and store everything as best as possible.” |

The ambassadors were not exaggerating: het Nederlandsche Paleys, or the Dutch Palace as the embassy building was called, completely burned to the ground in the years 1700, 1767, and 1831, suffered various other damages and could in some cases be spared only at the very last moment.

It took months if not years for the building and the ambassador’s possessions to be restored. Extensive correspondence on the unprecedented financial and practical complications of such an operation illustrates that the embassy personnel had to do their utmost to convince policymakers in The Hague to give financial support and empathy.

It was not self-evident for the Dutch embassy personnel to receive unlimited resources to carry out their duties properly. The cumbersome nature of the bureaucratic procedures compelled the ambassadors to think about practical solutions. Correspondence in the period between the two conflagrations of 1700 and 1767, reveals that the embassy personnel tried to limit the costs and diminish their dependence on the local authorities as much as possible.

From Dutch critiques on the Janissaries – elite soldiers who were also responsible for firefighting in the Ottoman Empire until 1826 – we understand that the members of this fire brigade were considered corrupt, violent, and chaotic. In some cases, embassies were forced to pay exorbitant prices to get a fire extinguished, while on another occasion it is reported that the Janissaries were amused by the chaotic situation and watched people running in different directions. The Dutch embassy personnel, therefore, tried to keep flames outside the perimeter walls of the Palace and, otherwise, extinguish the blazes with their own resources.

To save time and costs, the Dutch Palace asked for relatively smaller adjustments such as a private fire hose and a special canvas (brand zeyl) to cover the building and to distribute the water sprayed over the roof (dat men over het Dak van het Paleys dat seer groot is soude kunnen uyt breyden, ter wyl sulks met waater besproeyt…). More important was the expansion of a fire-proof storage room made of concrete (brandvrij magazijn) under the staircase. To get the construction of this costly cellar funded, instead of emphasizing the storage itself, the ambassador played the religion card, highlighting the need of a new chapel with fire-proof storage underneath.

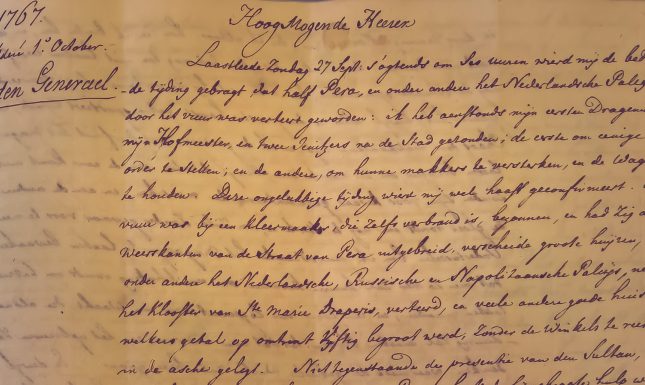

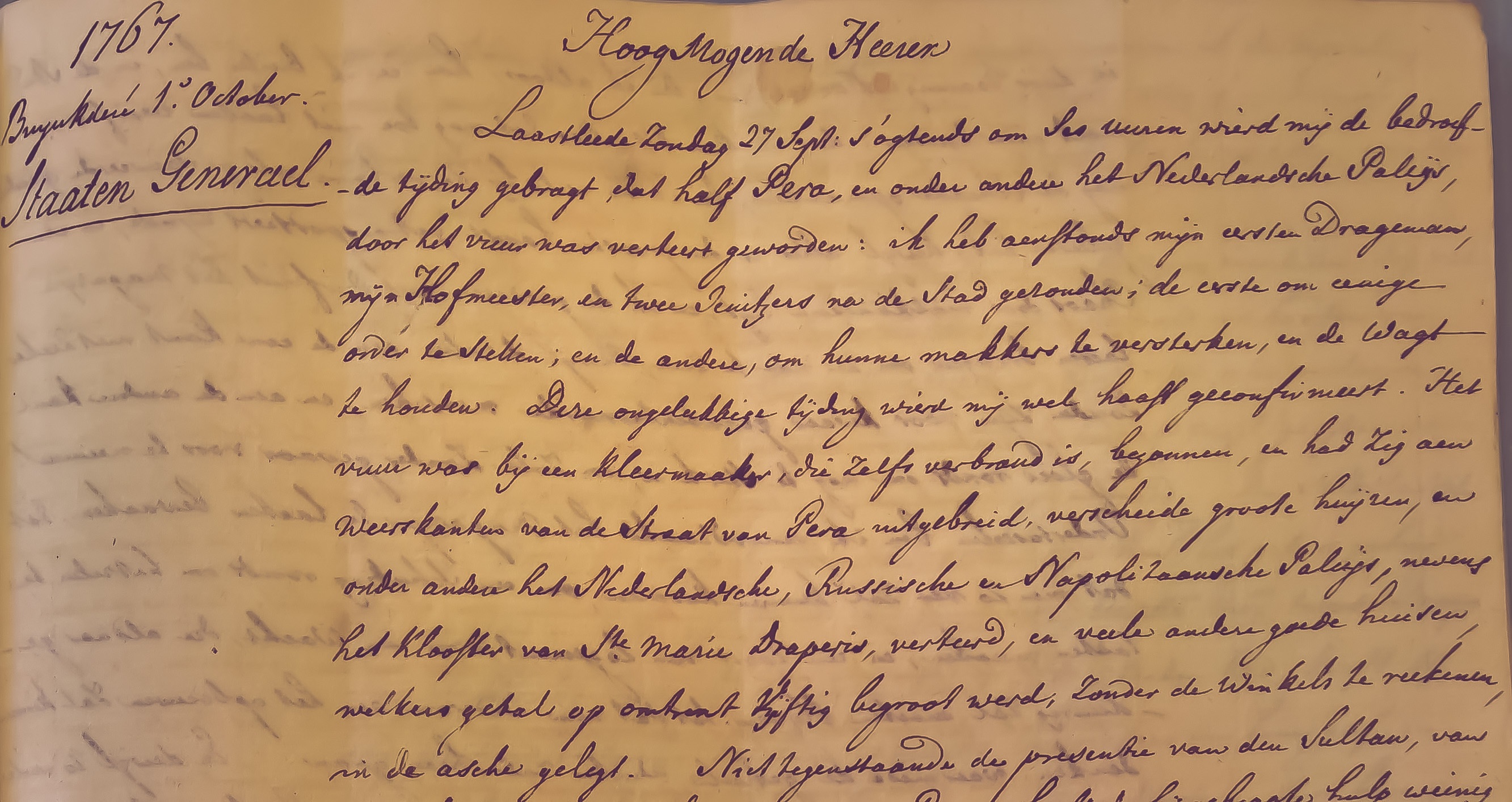

However, none of these measures was sufficient enough to keep the Dutch Palace from being destroyed by fires. After the building had burned to the ground in September 1767, in a long and emotional letter, sent on 3 November 1767, the ambassador Gerrit Willem Dedel explained with three arguments why the Palace needed to be rebuilt as quickly as possible. First and foremost, the Dutch Palace in Istanbul was a symbol of freedom for those in search of protection and asylum. Secondly, the chapel was essential for civil affairs such as marriage. Perhaps the most important but downplayed reason was that the rental house in which the ambassador stayed after the embassy had burned down, was on the first floor above a shop. It was an even more dangerous place, unprotected against flames and pestilence and without proper fire-proof storage. He argued that, in the long term, the frequent replacement of his valuable possessions and furniture would result in higher costs.

To substantiate his "heavy costs" (oneindig zwaerder dépenses) the ambassador gave examples of how other countries were also struggling with damage. The great fire of 1767 had also destroyed the rival Russian and Neapolitan embassies. However, the Russian empress had paid the costs the Russian embassy’s renovation and the Russians in Istanbul made an appeal to receive aid or at least temporary accommodation from the Ottoman state. The furniture of the embassy of Naples, on the other hand, was replaced by their insurance (assurantie). A couple of months later, in January 1768, the embassy personnel would this time complain about the doubled costs of living. Since the conflagration, the daily costs had increased from ƒ12 to ƒ30 day: “For half of that daily sum it is possible to live in The Hague or Paris."

Contrary to popular belief, the Dutch embassy was far from being an ivory tower from which ambassadors merely spied strategic information about the sultan’s lands. The Dutch residents of Ottoman Istanbul had to adapt themselves to local hazards and became from time to time the protagonists of social crises, such as frequent city fires.

Burak Fıçı studied Middle Eastern Studies at Leiden University, from which he graduated cum laude. His thesis is entitled "The Conflagrations of Ottoman Istanbul in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries According to Ottoman and European Sources."

2 Comments

Merhaba Burak Fıcı,

Afgelopen week kwam ik een heel dik boek van Lamartine tegen in mijn boekenkast. Het boek is minstens 150 jaar oud en in het Frans. Mijn opa kreeg het van zijn opa in 1907. Bij het doorbladeren bleek het voor de helft te bestaan uit een reisbeschrijving van een reis die Lamartine in 1832/1833 maakte naar het Heilige Land. Op de terugweg bracht hij een uitvoerig bezoek aan Constantinopel. Dit deel van het verhaal interesseerde mij omdat ik ooit zelf enkele jaren in Istanbul woonde. Tot mijn verbazing is de beschrijving van Pera behoorlijk negatief omdat het bijna geheel door branden verwoest was in 1833 en er desolaat bij lag. Je kunt je voorstellen met hoeveel plezier ik je artikel las over de branden in Istanbul en met name de toestand van het Nederlandse “paleis” omdat het mij ook duidelijk maakte wat de rol van de jenischaren was bij deze branden en de achtergrond van wat nu de Dutch Chapel heet. Ik heb persoonlijk leuke herinneringen aan het gebouw dat, begrijp ik nu, veel later gebouwd is dan ik dacht.

Kan jij Frans lezen ? Ik schenk je dan graag het boek, er is nog veel meer uit te halen. Vanwege een verhuizing ben ik grondig aan het ontspullen.

Geen idee of dit bericht je bereikt, maar vind het leuk als je reageert,

Met hartelijke groet,

Saskia Heikens

Beste Saskia,

Dankjewel voor het delen van dit interessante verhaal! Ik ben erg blij dat we op deze manier connectie hebben. Het lijkt mij leuk om een keer in contact te komen en hierover te praten. Ik informeer anders bij LUCIS naar je contactgegevens, als die daar bekend zijn.

Met groeten,

Burak Fici