Longread: Citi Yousoff’s Spiritual Journey and the Arts of Divine Calligraphy and Graceful Indifference

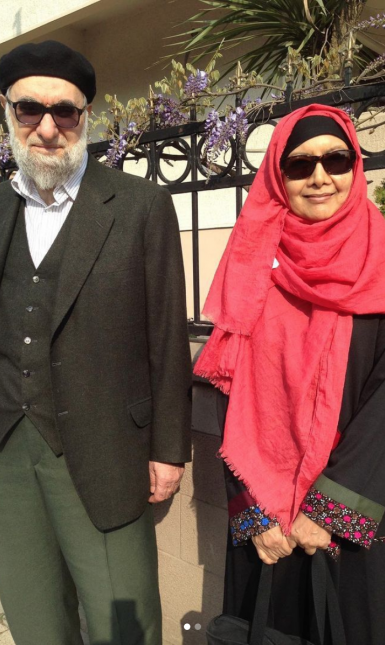

The loss of her daughter spurred Citi Yousoff onto a spiritual journey. It led her to study calligraphy with the renowned master Hasan Çelebi. Today she is one of the very few female calligraphers with an ijazah, a traditional licence. What drives her? And how does she view her position?

In 2000, Citi Yousoff’s 27-year old daughter – her only child – died of cancer. The loss catalysed a spiritual journey. Six years later, Citi travelled to Istanbul to study with Hasan Çelebi, a preeminent master of Ottoman-style calligraphy. In 2012, she was granted an ijazah, a licence that allows her to sign a work of calligraphy and to pass on her knowledge and skills.

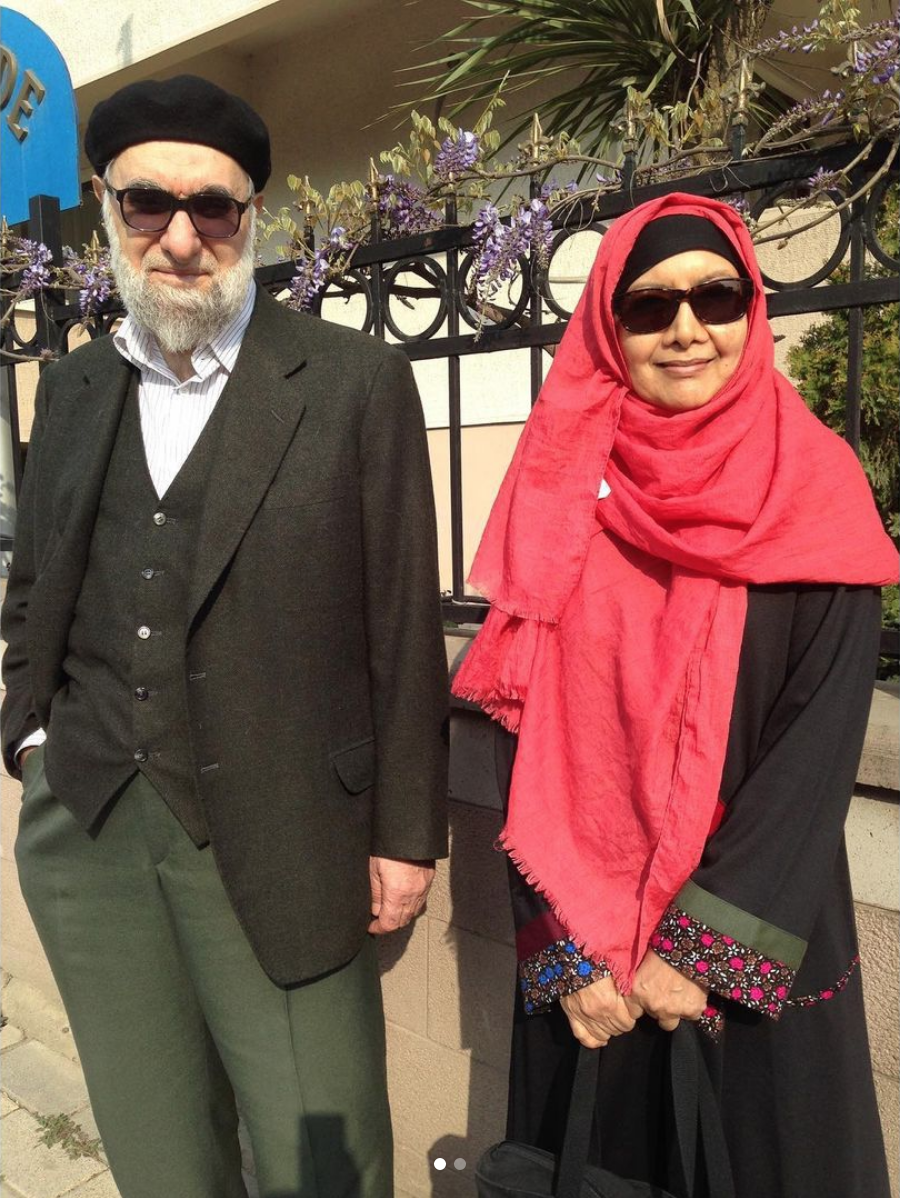

Today, Citi works in her country of birth, Malaysia. Since 2014, she has been teaching small but committed groups of students in the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. Two of her students have been granted ijazahs too, signed by Hasan Çelebi and herself. She has exhibited her work throughout the world, from London to Sharjah and Kuala Lumpur. She is one of a few traditionally certified women calligraphers. What drives her? Does her gender matter? And if yes: how, and why?

Citi Yousoff’s Spiritual Journey…

Citi was born in 1949 in Kota Bharu, in the Malaysian state of Kelantan. She was educated in an English-medium school founded and headed by her father, and she spent the final year of her secondary education in the elite Malay Girls’ College boarding school (currently the Kolej Tunku Kurshiah) in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan. Such a prestigious school, she reasoned then, should bring her closer to her goal: get out of Kelantan, become rich and successful, and take control of her life.

A couple of jobs in the insurance and travel industries and a short, unsuccessful marriage later, she was a single mother with few options. But she was enterprising and opened an antique shop. Toddler in the car, she travelled around the country – and even to China – for new wares. She liked it, but the business was slow. “So I went into property development. This was more lucrative.” It was the 1980s and Kuala Lumpur was turning into a booming Asian metropole.

In 1986, Citi sent her daughter to a boarding school in London. Two years later, her bank went into liquidation and Citi was told to clear her loans, meaning that she had to sell much of her property below value. Disillusioned, she changed course. She joined her daughter in London and decided to pursue an artistic degree. “By God’s grace, I had enough left to do this.” She was accepted by the Wimbledon’s College of Arts, where she majored in painting. When her daughter had finished her studies in art and fashion, they worked together for a while, with Citi buying up new estate and her daughter designing and decorating before they sold it off again.

“When you lose your parents, it is acceptable. When you lose your child, it is not. It was (…) half of me gone.” Encouraged by a friend, she did the Umrah, the non-obligatory visit to Mecca. The next year she went on Hajj, the mandatory pilgrimage. “The next year I went again, for my daughter. The year after, again, for my mother.” She deepened her search. “I felt like God didn’t love me. He took my daughter way. I didn’t understand. I wanted to know where I had gone wrong. (…) When God wanted [the Prophet] Moses to serve him, he made him suffer. I submitted to Him, like Moses submitted to Him. (…) I am not a prophet. (…) But I stay close to Him so that He may keep me on a straight path back to him.”

Citi was a painter. “I decided that whatever I did should not keep me away from God. So I put the Quranic text, the Revelation, in my work. I painted it. But I thought it wasn’t professional. So I decided to do a Masters in Islamic art.” In 2004, she entered The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London. She learned about sacred geometry, painted icons, illuminations, Islamic motifs, different kinds of tile making, and stone carving. In the summer she went back to Malaysia to learn traditional Malay woodcarving. “All by hand. A beautiful course. It was very good for me. I needed it to get up each day.” But it was tiring, too. And there was no calligraphy. “The core of Islamic art. I studied all this. And I was missing the core.”

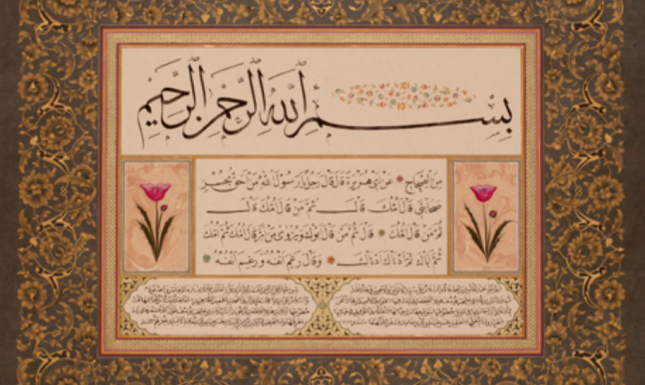

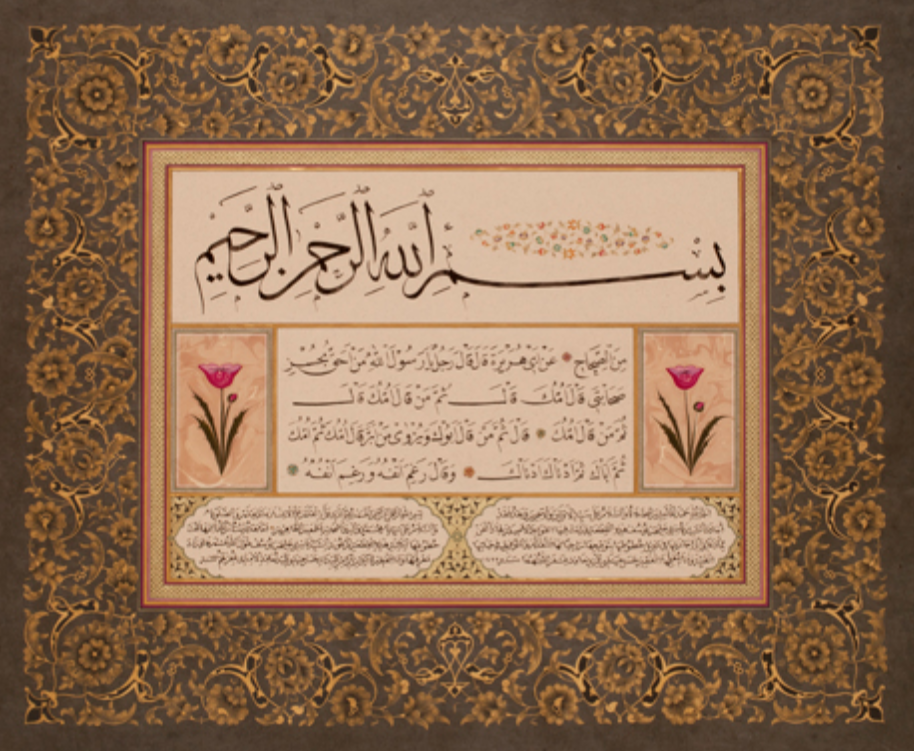

On her graduation day, in 2006, she sold one of the last paintings she made – two horses in miniature style – to Prince Charles. By that time, her head was already elsewhere. In Istanbul, Hasan Çelebi had accepted her as his student. For six years, Citi travelled there regularly to learn from him, until, in 2012, she succeeded in obtaining the ijazah in the Thuluth and Nashk scripts.

…and the Arts of Divine Calligraphy…

The reader may have guessed by now that Citi’s account – on the search for beauty and the love of God – is thick with sufi valences. One of her teachers at the Prince’s School was the writer, philosopher, sufi master, authority on the work of Shakespeare, and renowned biographer of the Prophet Muhammed, Martin Lings. She was hoping to be guided by him but he died in 2005 at the venerable age of ninety-six. “But they say a sufi master finds his own followers” and ultimately Citi was found by the London-based Indian-born Shaykh Hazrat Azad Rasool. Today, Citi coordinates the first Malaysian branch – consisting of some forty followers – of the Naqshbandi Mujaddidi order.

The history of Islamic calligraphy, Annemarie Schimmel has shown, is steeped in sufism. “The sentences of the Prophet,” she writes in one of her Kekorvian Lectures on the subject, “or, in later times, the sayings of some of the saints could fill the house of the owner of a fine piece of religious calligraphy with baraka [blessings]. (…) As in Sufism, a silsila, a spiritual chain, was absolutely necessary to connect the discipline through generations of masters with the founder or with the most famed writer of his particular style.” Sufism demanded a calligrapher to be pure of heart, moreover, “of sweet character and of an unassuming disposition” (Calligraphy and Islamic Culture, pp. 36-37).

In Citi’s account of her apprenticeship, artistic techniques and the training of character blend together. The character of the guru is an “imposing factor,” she explains, and Hasan Çelebi is “not an ordinary man.” He is a virtuous person. “Full of love for everyone. (…) A man of akhlaq (ethics, disposition), like a prophet.” Training in calligraphy is about purification, contemplation, and emulation of style and character. Calligraphy is a blessing (baraka) and what is transmitted in training is blessing translated to technical skill.

“By making the art... When I went to him, I was like a rough stone. He helped to polish me. Polish me until I was shining. Purifying me. Showing me where I went wrong, every time. [It was about] getting refined. My inner. My outer. My sense of observation. My patience. Everything gets refined. [Everything] gets better.”

…and Graceful Indifference

In what is certainly an extraordinary coincidence, given the fact that so few women find their way into the discipline, another contribution on a woman calligrapher was published on this very blog just a few weeks ago. As Delaram Hosseinioun points out, the Persian artist Pouran Jinchi uses calligraphic techniques to reassemble words and texts. “Through her modern and radical approach, Jinchi deconstructs all the classic calligraphy norms and renders a new artistic and feminine soul to the words.” In Jinchi’s conceptual art, words become “illegible.” They are turned into an “aesthetic chaos,” luring her spectator in “a mesmerizing visual vortex.”

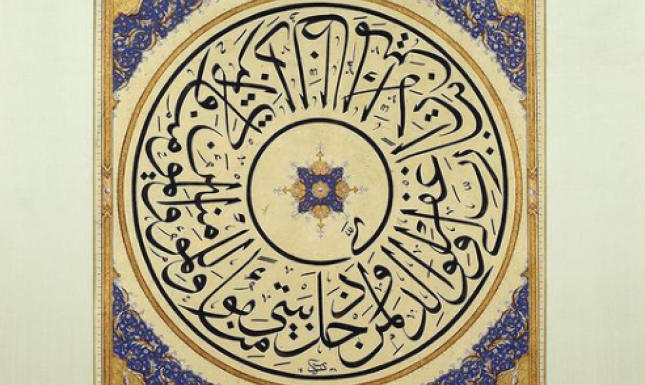

In Citi’s practice, this would be unthinkable. By this I do not mean to say that she is averse to modernizing her art, although she prefers to speak of “contemporizing” instead. When we first met, in 2016, she was experimenting with expressive techniques and various levels of transparency to show her audience the “flow of the ink.” “I want to highlight that part of calligraphy. (…) Put stress on the things that are taken for granted.” By emphasizing the nature and qualities of the material she wants to “emit sensations, touch the viewer’s heart.” She hopes to enable the spectator to follow “where the hand has gone” and thus “feel connected to Him.” To move the viewer, if only briefly, “away from this world” (dunya).

But in line with the same aim, Citi sets clear limits to her experimenting. Traditional art is not static, she maintains, “but the science and the rules don’t change. (…) There are boundaries.” Choices pertaining to the spacing between letters, overlaps and crossovers, and symmetry are subject to rules. Most importantly, she says, “it should be easily read. (…) [It must be] continuous from beginning to the end.” Strict norms guide compositions that are not based on a straight line. “It has to be a text that is easily read. Because you don’t want people to misread the word of God. It has to be clear.”

The same “science and rules” have allowed Citi to insert herself into the authoritative genealogy of Hasan Çelebi and from him all the way down to the great Ottoman calligraphers of the past. Here it is important, as David Simonowitz has argued in an article on Hilal Kazan, another one of Hasan Çelebi’s few women students that were granted an ijazah, to look beyond the sufi dimension of calligraphy. For the recognition of traditional calligraphers is contingent on the “complex genealogies of transmission” through which the Islamic tradition, as a whole, is authorized and continued.

When I asked Citi whether, in the almost entirely male-dominated context of traditional calligraphy, her gender has posed any problems or constraints, she was surprised. She had never given it much thought. And anyway, the answer was no.

To a large extent, this reflects Citi’s social position as an independent and cosmopolitan figure: a successful businesswoman-turned-artist and spiritual guide. At the same time, it is evidence of the artistic confidence and status bestowed on her through the ijazah, her teacher’s licence. “In the Islamic world (…), women are not equal to men. But I am not interested in taking the place of a man. I am only interested in taking the place of a calligrapher. I don’t even want to talk about being a man or a woman. If [people] don’t recognize me… It doesn’t matter to me. (…) I am not a boastful person. (…) God will put you in the right place. It is not an issue for me.”

When I asked her about the ijazah, and whether a woman might be seen as a weaker link in the chain of transmission, she was equally adamant. “No,” she said. “Never. It is the same. This is the strength of the ijazah. And of the teacher. That I was taught by Hasan Çelebi. It is enough. No one dares to say [anything]. It is the work that speaks for itself. It is not the glory I’m after.”

0 Comments